Emerging in the United Kingdom in the mid-1950s and pioneered by progressive artists Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton, the Pop Art movement wouldn’t be truly defined as such until it moved to the US in the 1960s.

New York artists such as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, and Claes Oldenburg started defining what would become an international phenomenon, creating works inspired by mass culture, everyday objects, and the cult of celebrity in a bid to blur the lines between high-art and low-culture.

How did Pop Art influence society?

This exciting new wave of artists would focus their attention on themes that spoke of the mundanity of real-life and of mass society. Art would frequently incorporate commercial images, at a time when capitalism was exploding after war-time austerity.

From here Pop Art would go on to become one of contemporary art’s most instantly-recognisable styles. It then began to find its way into fashion and music scenes, before paving a path for younger artists who would grow up on a diet of consumerism and over-saturated popular culture.

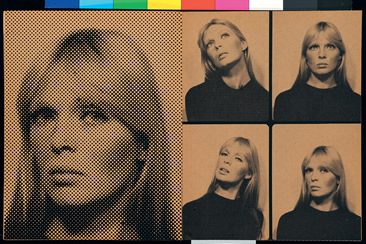

Fashion Plate, 1969-1970, Photo-offset lithography, collage, screen print in two colors, pochoir, retouched with cosmetics by the artist on Fabriano paper. 99.1 × 68.6 cm

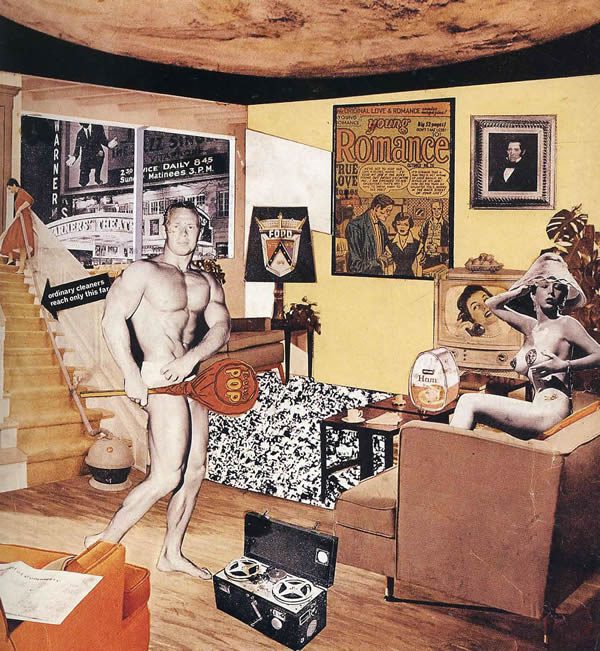

Richard Hamilton, Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? 1956, 26 cm × 24.8 cm, Located at Kunsthalle Tübingen © the artist

Richard Hamilton

Born in London in 1922, Richard Hamilton was an art visionary who had immersed himself in movies, television, magazines, and modern music. He outlined ideals and introduced the perception of the artist as a consumer and contributor to mass culture.

The artwork of Hamilton had a drastic influence on several industries, including the gambling industry. This great post to read about online casinos demonstrates how many online casinos use graphics based on contemporary art in order to lure more customers with the use of arresting visuals. It is also worth mentioning that such graphics have a positive effect on the gaming experience.

Despite Warhol going on to become Pop Art’s household name, credit should fall at Hamilton’s door for laying the foundations on which he would build his art empire. The Brit’s 1956 collage, Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?, was the first work in a fledgling genre to achieve truly iconic status.

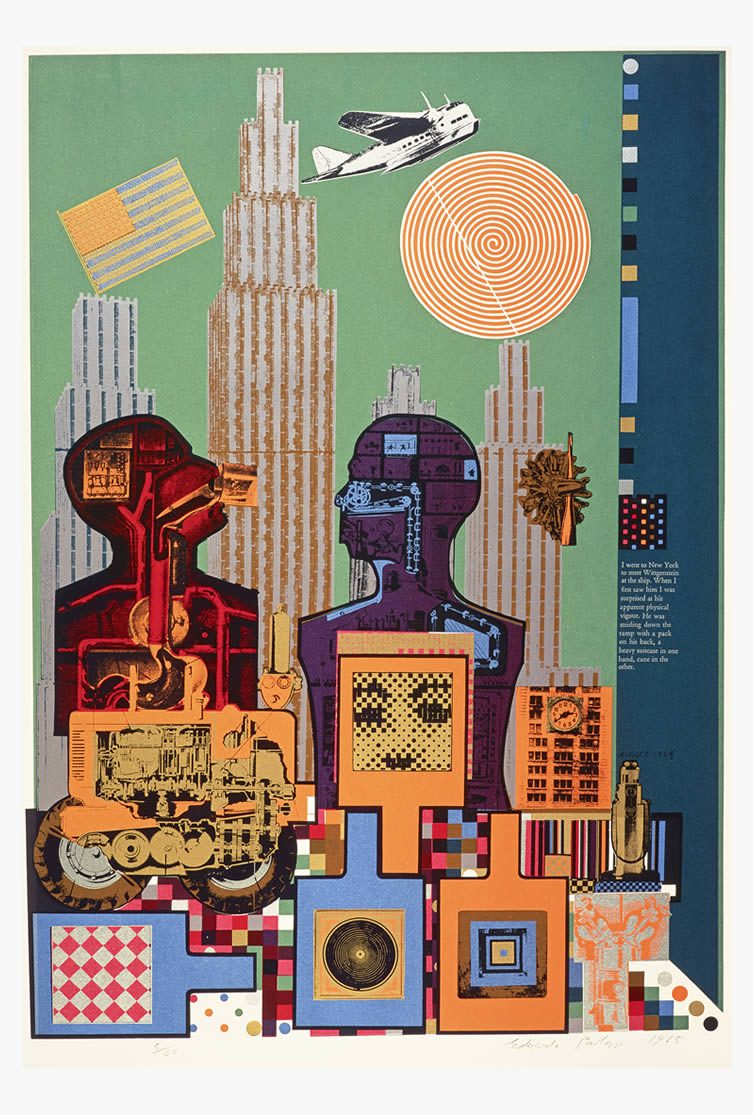

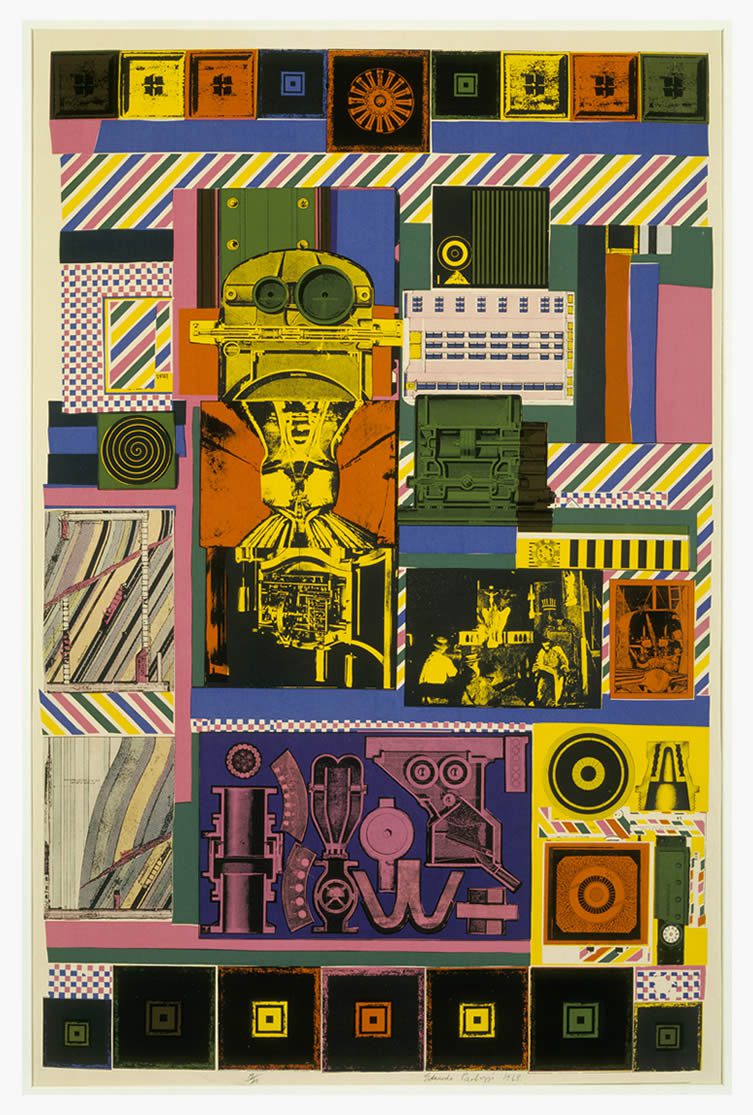

Eduardo Paolozzi, Wittgenstein in New York (from the As is When portfolio), 1965. 76 x 53.5cm Courtesy Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art © Trustees of the Paolozzi Foundation, licensed by DACS

Eduardo Paolozzi, Conjectures to Identity, 1963–64. Screenprint. 79.5 x 52.5 cm British Council Collection Courtesy the British Council Collection © Trustees of the Paolozzi Foundation, licensed by DACS

James Rosenquist, President Elect, 1960–61/1964. Oil on Masonite. 7′ 5 3/4″ x 12′ (228.0 x 365.8 cm) [89 3/4″ x 144″] Centre Georges Pompidou, Musée National d’Art Moderne/Centre de Création Industrielle, Paris [AM 1976–1014].

Individual styles

Although their individual styles would vary, all Pop artists shared ground in their choice of the iconography of popular culture as fundamental to their work. Hamilton and Eduardo Paolozzi with their meticulously layered collage work. Warhol and his preoccupation with repetition; early Coca-Cola bottles and Campbell’s soup tins.

It was these tins that were produced as if the work were a supermarket shelf. Meanwhile, James Rosenquist, another New York-based Pop pioneer, a fan of political messages by way of recontextualising magazine clippings in colossal collage paintings.

Hopeless, 1963, Kunstmuseum Basel, Depositum der Peter ud Irene Ludwig Stiftung, Aachen

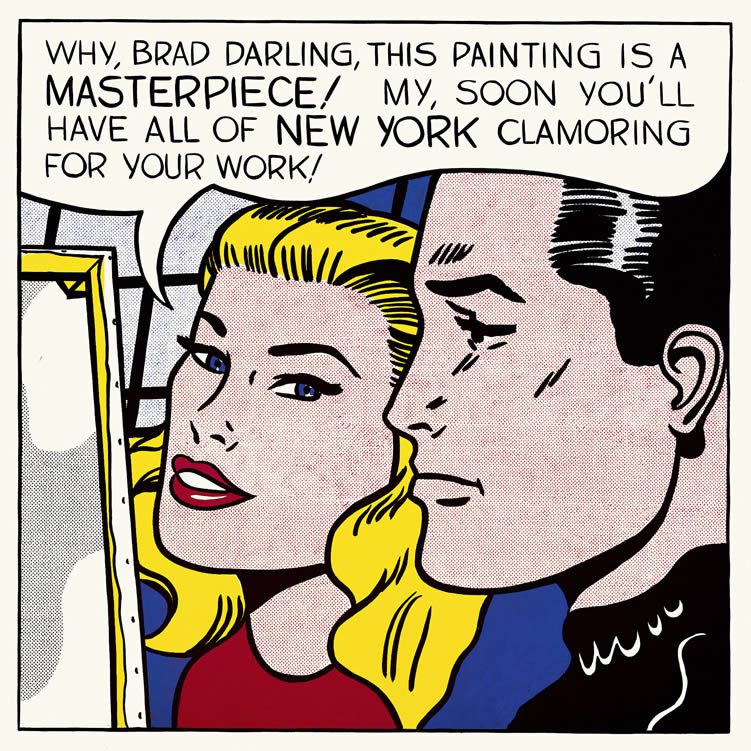

Masterpiece, 1962, Private Collection © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein/DACS 2012

Roy Lichtenstein

Roy Lichtenstein made his mark by appropriating images from comic books to create his own paintings. (This was not without much controversy, and to the frequent disgruntlement of the original artists.)

His hand-painted Benday dots often portrayed protagonists as trapped in melancholic situations, with expressions from gnawing dissatisfaction to outright misery.

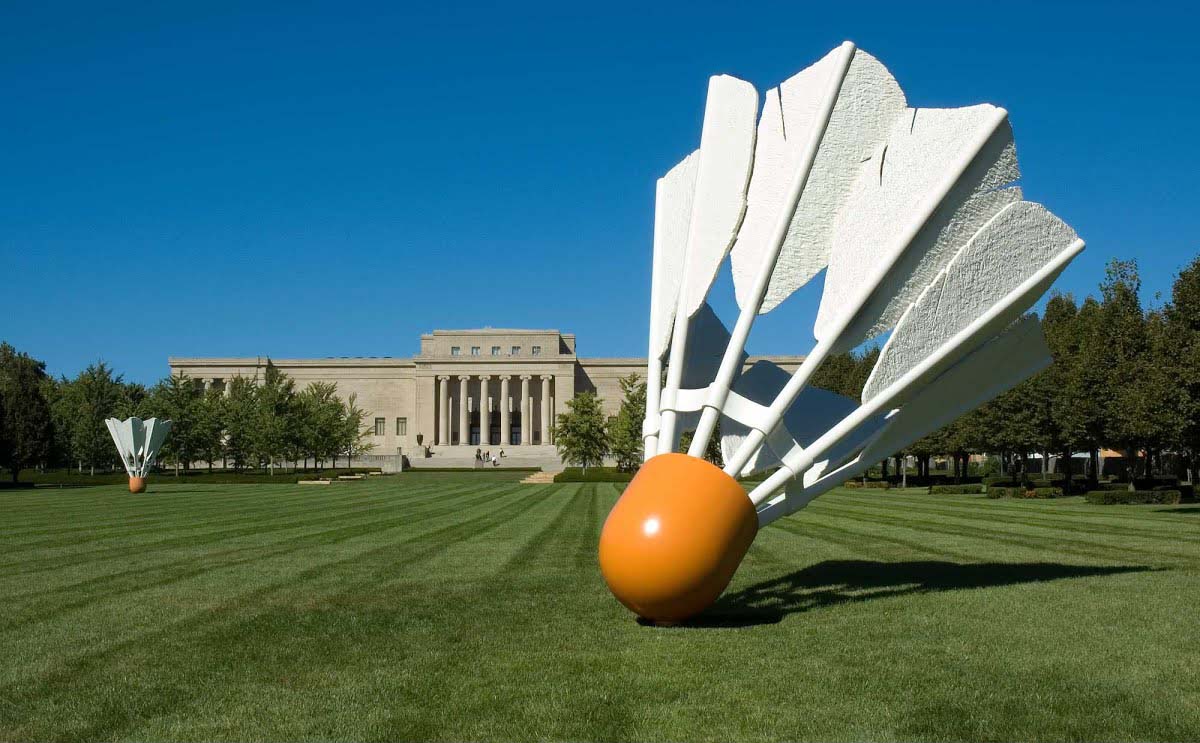

Claes Oldenburg, American (b. Sweden, 1929), Coosje van Bruggen, American (b. The Netherlands, 1942-2009), Shuttlecocks, 1994.

Photo, Keith Ewing. Sculpture Park, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City

Claes Oldenburg

Stockholm-born American artist Claes Oldenburg would become a key figure too. Renowned for crafting large public sculptures, Oldenburg’s 45-foot-high Clothespin (1974), located at Philadelphia’s Centre Square office complex, and 1992’s series of Shuttlecocks, dotted around the sculpture park of Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, changed the face of contemporary public art.

His ‘soft sculptures’ of food and mundane inanimate objects blurred realities. “I am for an art that takes its form from the lines of life itself,” he once said, “that twists and extends and accumulates and spits and drips, and is heavy and coarse and blunt and sweet and stupid as life itself.”

As the art world shifted from art objects to installations throughout the 1970s, the Pop Art movement waned. That was until mass media-obsessed artists such as Jeff Koons and Takashi Murakami lead the way with a renaissance branch of the Pop Art movement that would be dubbed Neo-Pop.

Jeff Koons, New Hoover Convertibles Green, Blue, New Hoover Convertibles, Green, Blue Doubledecker, 1981–87 © Jeff Koons.

Jeff Koons, Moon (Light Pink), 1995–2000 © Jeff Koons.

Takashi Murakami, Hustle’n’Punch By Kaikai And Kiki, 2009

acrylic and platinum leaf on canvas mounted on aluminum frame

118 1/8 x 239 3/8 x 2 in. (300.04 x 608.01 x 5.08 cm)

Other inspirations

Koons, like Duchamp had done before him, takes his inspiration from items not typically considered fine art. Inflatable plastic toys, basketballs, and vacuum cleaners find their way into galleries as a kind of Pop-meets-readymades. There was again a sense that anything popular was fair game. From cartoon caricature to mass-produced ephemera, Pop was back. (Had it ever truly left?)

Murakami, meanwhile, is a Japanese artist famed for his psychedelic forays into comic-style graphic art. It has been said to ‘use and abuse’ the confluence between high and low art. Murakami’s over-saturated fantasy worlds draw their inspiration from Japanese popular culture, in a sort of cycle of pop movements.

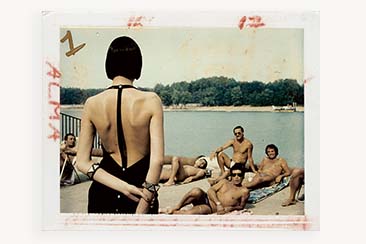

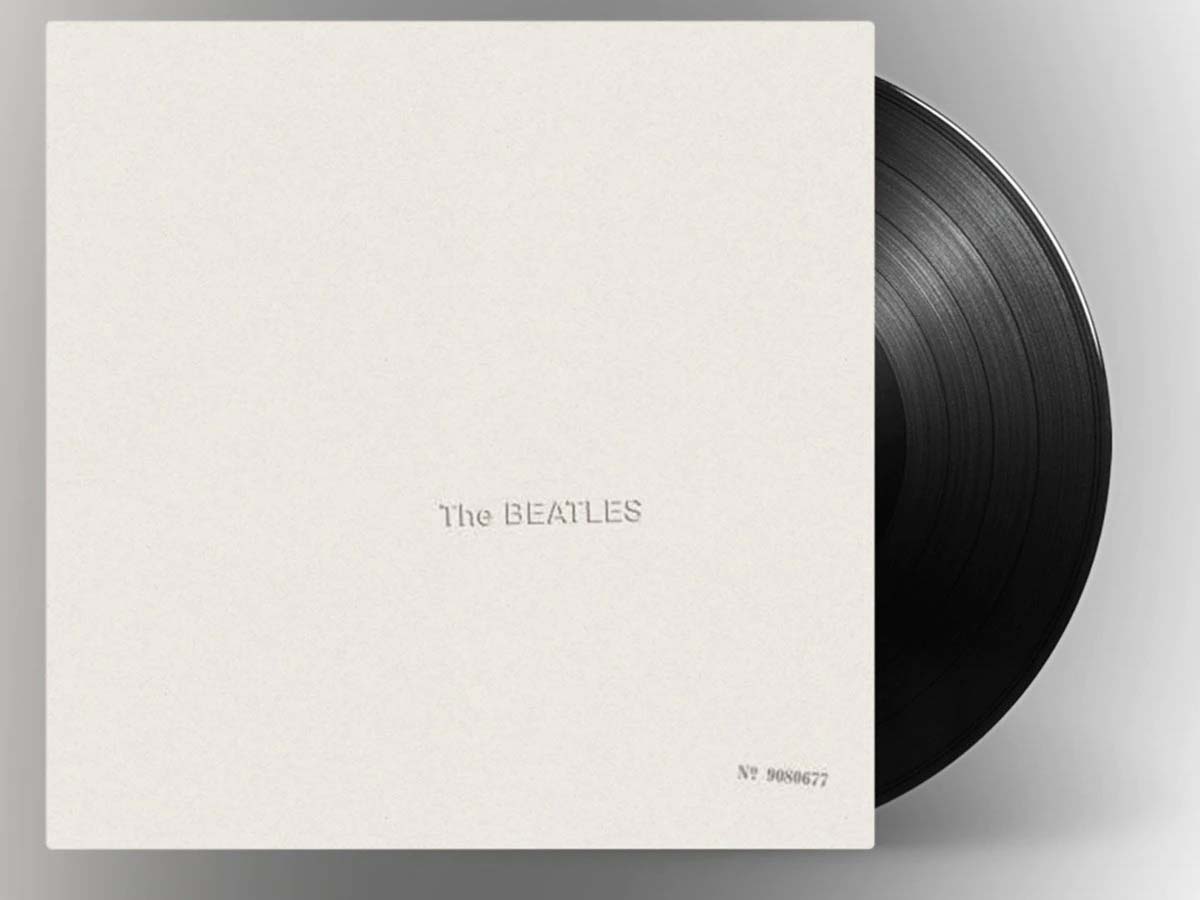

Richard Hamilton for The Beatles, 1968.

The Pop Art movement’s musical side

Ironically, Pop Art’s touching points from popular culture would turn the full cycle. The art movement would itself have its own place in mass media. In 1968, Richard Hamilton designed the cover for The BeatlesPeter Blake’s offering for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, each demonstrating the broad diversity in an aesthetic that had emerged in the Pop movement.

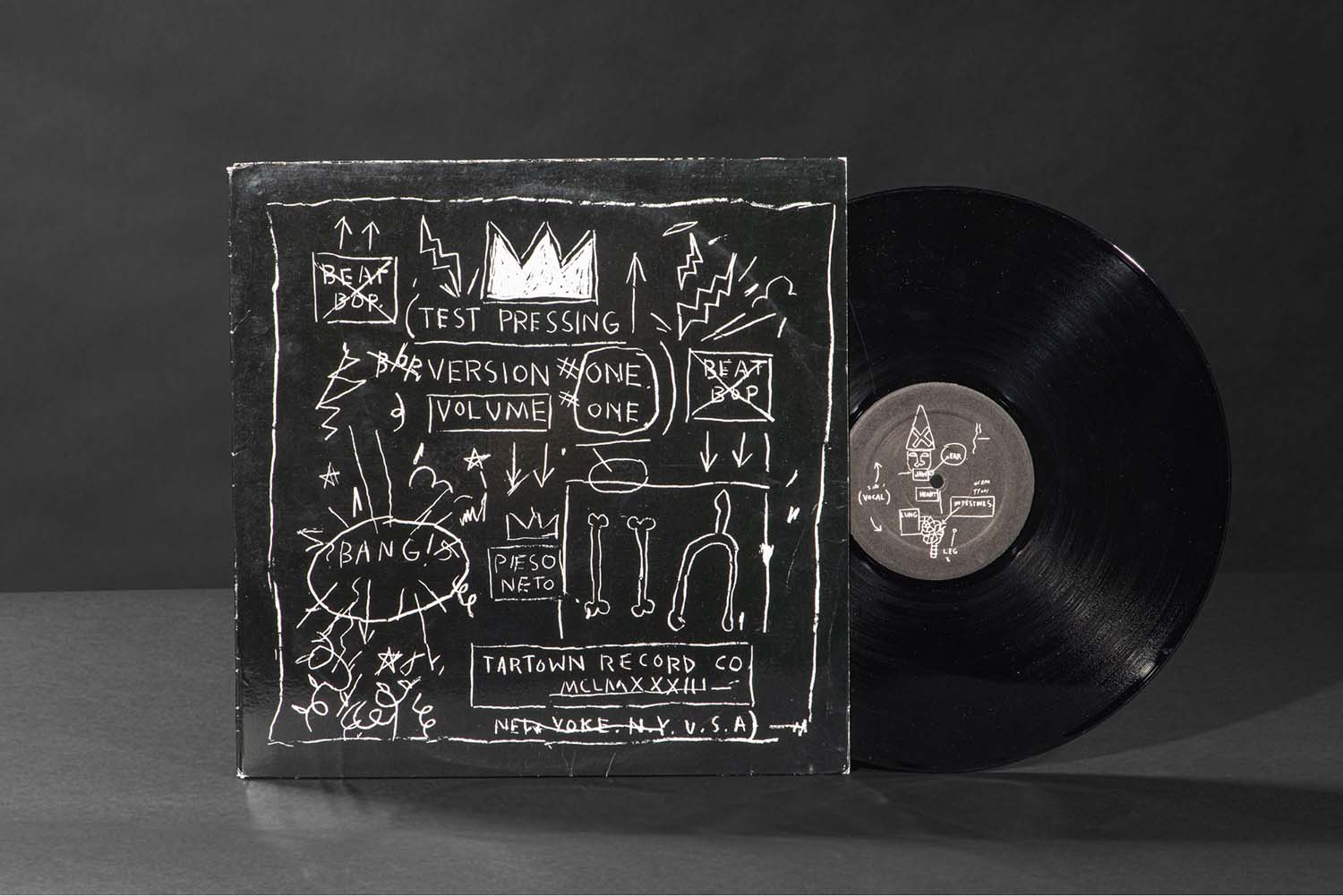

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s artwork for Rammellzee and K-Rob’s Beat Bop.

The blueprint

Fusing influences from hip hop, punk, and street art culture with the Pop sensibilities of his friend Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat neo-expressionist style demonstrated how the Pop Art movement’s influence could contort into new and refreshing distortions of its original aesthetic.

The Brooklyn-born artist’s frenetic aesthetic would serve as a blueprint for many graphic artists that followed. The sleeve for experimental hip hop stars Rammellzee and K-Rob’s 1983 single, Beat Bop, would see the artist create one of the very few commissions he completed during his lifetime.

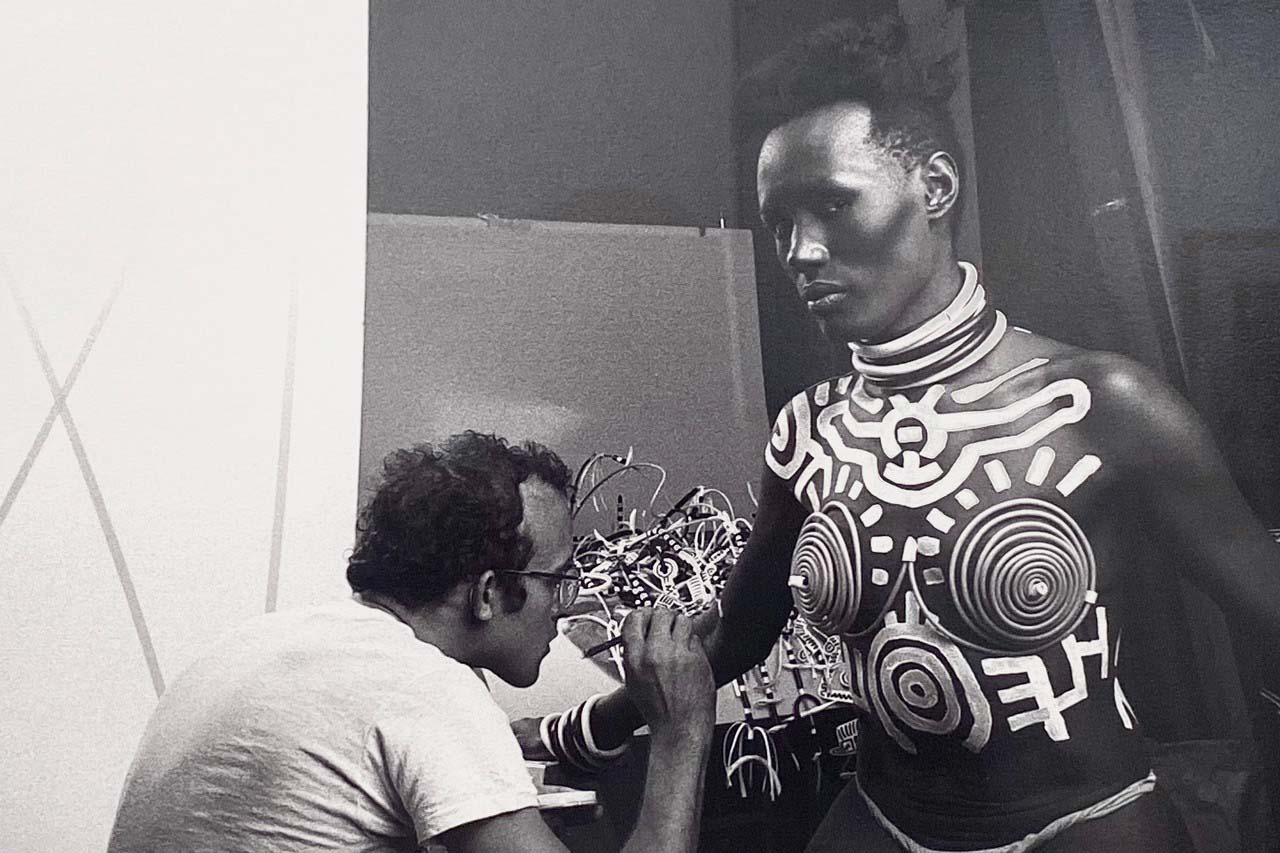

Keith Haring painting Grace Jones for her 1986 video, I’m Not Perfect (But I’m Perfect For You).

As the scene inspired an entirely new generation of artists, Los Angeles-based Kenny Scharf would emerge from the interdisciplinary East Village art scene during the 1980s. Alongside Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, he designed the cover art for the B-52’s fourth studio album, Bouncing off the Satellites

Haring himself, meanwhile, painted onto Grace Jones’s famously Amazonian body for the 1986 video of I’m Not Perfect (But I’m Perfect For You). Andy Warhol would make a fleeting appearance.

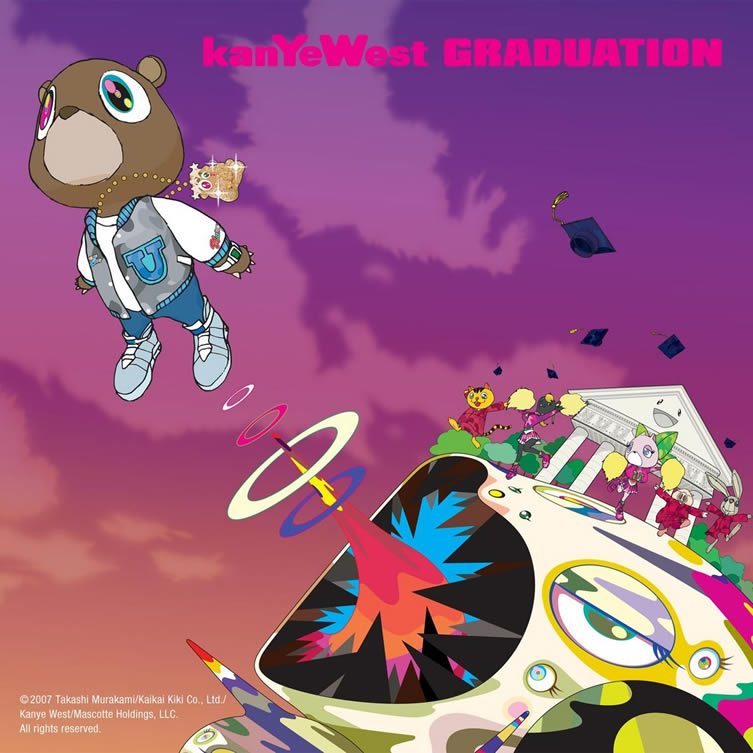

Takashi Murakami for Kanye West, Graduation, 2007

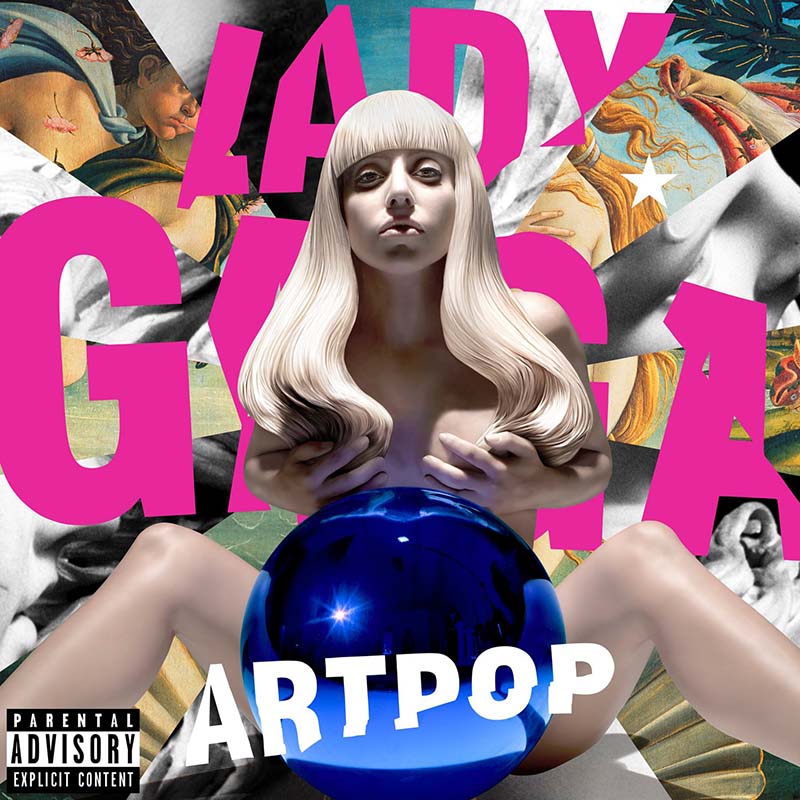

Jeff Koons for Lady Gaga, Artpop, 2013

A continuing trend

More recently, Murakami designed the cover for Kanye West’s 2007 album, Graduation. The artist using his signature style on West’s ‘dropout bear’ mascot, showing him leaving the fictional college Universe City. In 2013, Koons handled the artwork for Lady Gaga’s Artpop album, creating a lifelike sculpture for the release party in New York.

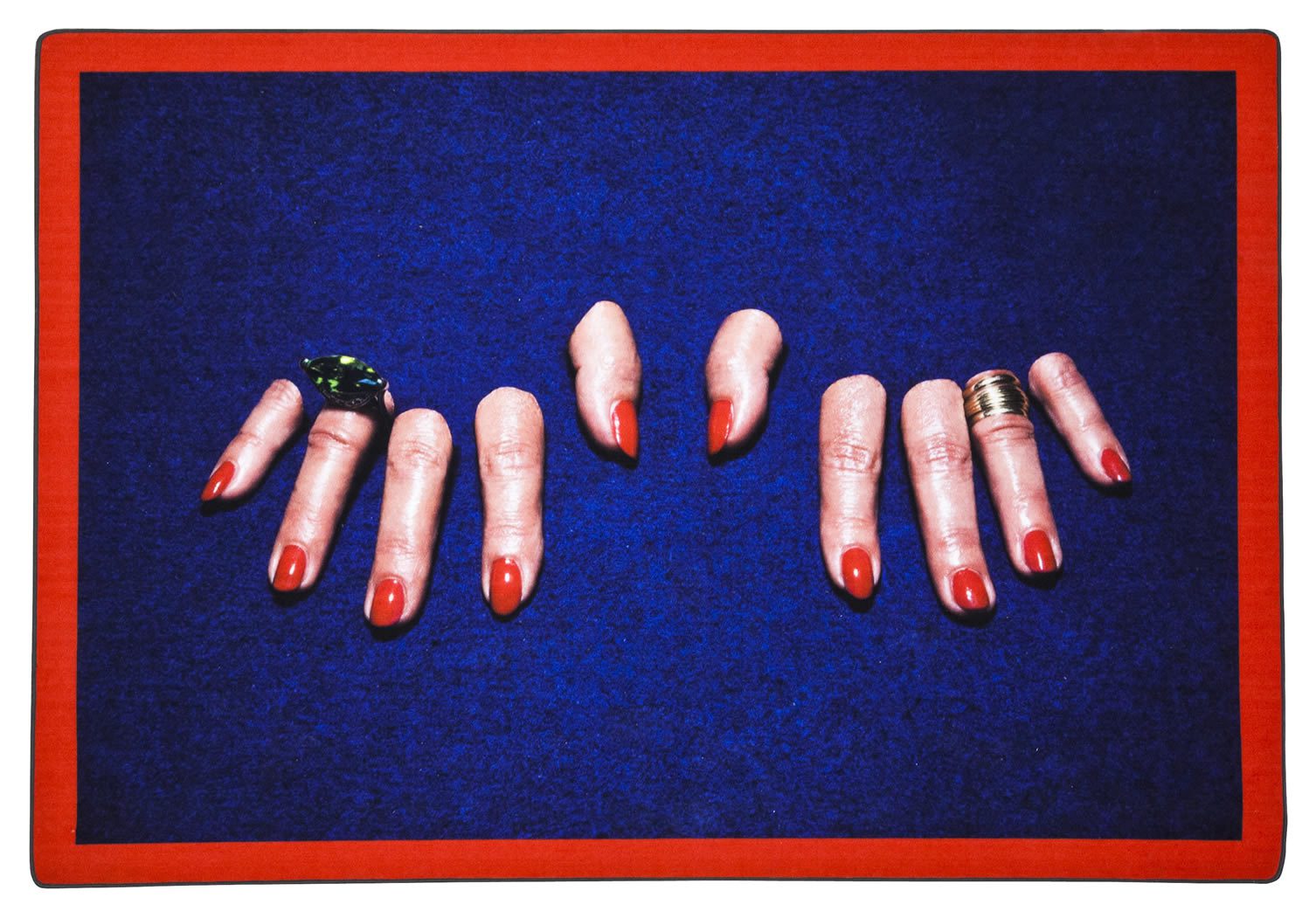

SELETTI wears TOILETPAPER (Maurizio Cattelan & Pierpaolo Ferrari) at Galerie Perrotin.

Courtesy ToiletPaper, Seletti & Galerie Perrotin

Contemporary Culture

Permeating all aspects of contemporary culture, the resonance of Pop can be felt from interior design—Italian labels Seletti and manufacturer Gufram of particular note, bold pieces like Studio 65’s Bocca chair defining the culture crossover—and throughout all aspects of graphic art and marketing.

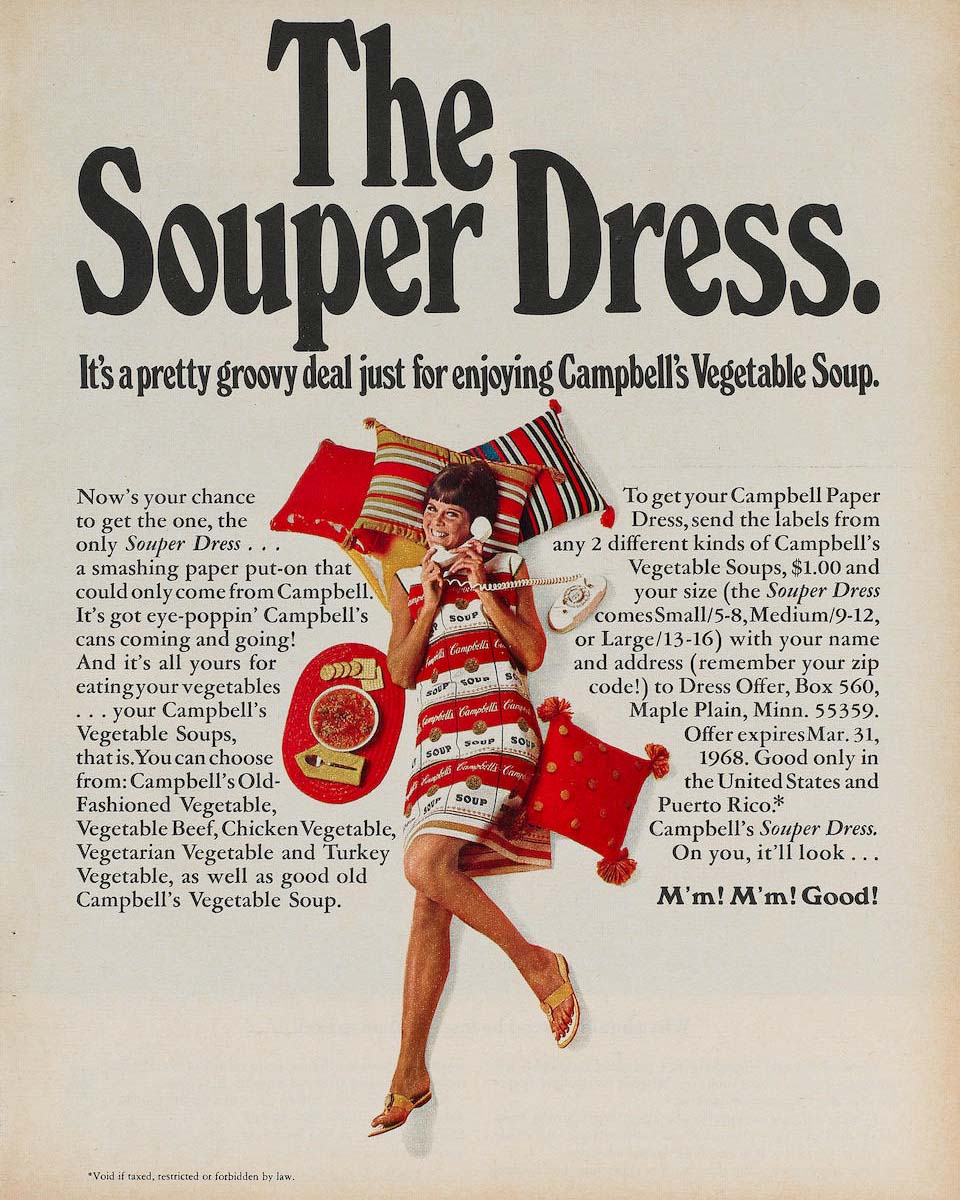

Andy Warhol, The Souper Dress, 1966–67

Purchase, Isabel Schults Fund and Martin and Caryl Horwitz and Hearst Corporation Gifts, 1995

Cross-Pollination

With a long history of cross-pollination, the worlds of art and fashion have collided regularly in the decades since Pop Art began. Yves Saint Laurent co-founder Pierre Bergé once offered the following ditty: “fashion is not art, but it needs an artist to create it”, and the two disciplines have frequently bled into one another.

Warhol’s The Souper Dress was itself a bona fide art-cum-fashion crossover. Lichtenstein’s comic book take-offs have been favoured by all from Nike and Converse to New York fashion darling Lisa Perry, who is quite the Pop Art obsessive, her apartment an ode to the movement. “There are no walls left,” she admitted last year, having been collecting works from the scene for close to 20 years.

“I don’t want to ever put anything in storage and sometimes we’ve swapped things out, but the collection is at a place that is, we’re really happy with it. Pop Art has skyrocketed. It’s a whole different world from 2000. So we’re very happy with what we have, what we were able to get. For some other homes and for my kids, we collect younger artists and still look for different places, but this home, we’re good.”

Philip Colbert’s The Rodnik Band

Further Collaborations

Takashi Murakami too has collaborated with numerous brands. Vans and Louis Vuitton to name just two. Whilst Koons has collaborated with the high street brand, H&M. This collaboration saw a collection of bags emblazoned with his signature balloon dog.

There are also contemporary fashion designers who have taken Pop’s inspiration and ran: Philip Colbert (who earned himself the sobriquet of ‘godson of Andy Warhol’ by Andre Leon Talley) with his Poptastic label The Rodnik Band, and provocateur Jeremy Scott, whose junk culture-inspired work for Moschino is as Pop as it gets.

© Ben Frost

Alex Chinneck, From the knees of my nose to the belly of my toes

Alex Chinneck, Under the weather but over the moon

Alongside fashion designers, contemporary artists also continue to absorb the impact of those mid-century pioneers. Names like Ben Frost, who sits somewhere between the antagonism of Jeremy Scott and consumerist ideals of Warhol. Alex Chinneck, meanwhile, embraces the counterculture public art spirit of Claes Oldenburg. His large-scale surrealism embodies the quintessence of the Pop Art movement.

Where is Pop Art today?

As the world continues its downward spiral into the depths of mass consumption, Pop Art continues to thrive on the same cultural values that led to its timely genesis. As long as there is mass media there will be creativity fuelled by the introspective values of your Paolozzis, Hamiltons, and Warhols.

Galleries continue to curate huge retrospective exhibitions of the scene’s true pioneers, and we continue to see influences across other cultural plains.

A perpetuation of low- to high-culture, the Pop Art movement seems to be set on a loop every bit as repetitive as Warhol’s most famous work. But like the great man said: “Isn’t life a series of images that change as they repeat themselves?”