I am, I will admit, not a little daunted as I prepare to speak to Phillip Toledano. Every interview has its unique challenges, but this one more than most. How does one approach a famously impish self-deprecator whose projects are so diverse as to include a moving documentation of his father’s final decline (Days With My Father), a meditation on the relics by which his mother remembered his sister who died in childhood (When I Was Six) – and the hilarious Kim Jong Phil, in which the artist inserts himself as the star in various dictators’ self-portraiture follies?

From the series Days With My Father

Asking about the family traumas at all seems a bit insensitive, and even if I do manage to avoid seeming exploitative I’m doubtful of eliciting a straight response. I’ve conducted interviews where questions about the artist’s private life were met with a stare so withering it was as if I’d suggested, apropos of nothing, that we might meet at some point over the summer for a long-weekend wrestling horses in Mongolia; my fear is this will be one of those.

On the contrary, as it turns out: Toledano is charm itself, and very forthcoming. Tentatively, I ask first about Days With My Father, the series of photographs (eventually a book) of his memory-loss-stricken father’s last years. Was his subject aware of what was going on?

I insist, ladies first.

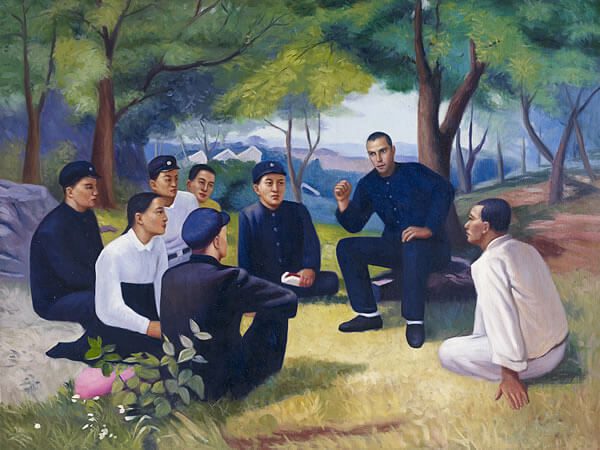

Oil on canvas, 30 × 40 inches

From the series Kim Jong Phil

‘Yes, he certainly was aware of what I was doing. He’d ask to see the images, which I’d show him on my iPhone, and then he’d tell me they were terrible! My father liked the idea of the work, actually, just not so much the results — as I mention in the book, he was remarkably vain in some ways! But he worked with me anyway, holding still for the camera and doing what I asked him to do, although never for long — four or five shots and then he was done.’

From the series Days With My Father

It gets more poignant. With no short-term memory, after the death of Phillip’s mother Toledano Sr. had no way of sustaining the knowledge of her passing; he was constantly perplexed by the inexplicable absence. So, after repeated bereavements that could have continued indefinitely, Phillip explained that she had gone to Paris to look after her ailing brother, a gentle lie that lasted until the end. Throughout the book I was reminded of a line from T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land — ‘These fragments I have shored against my ruins’ — and of the sequence in King Lear during which Edgar lies to his father to keep him from suicidal despair. Do those associations make any kind of sense? I ask.

‘It makes a great deal of sense. That process was like trying to hold onto sand, impossible yet inevitable. I did it to remember, I did it for me in that sense, to help me hold on. Yet ironically I never look at the images, I just remember the memories themselves. I think it was also an act of survival for me, in some respects — a way of imposing sense on something utterly senseless.’

From the series When I Was Six

When I Was Six is an equally heartbreaking series that meditates with profound, loving mournfulness on both his mother and his lost sister. I’d love to ask him about that, too, but I’m wary of dwelling too much on these kinds of autobiographical elegies when the work is so much more varied. So I decide to move the discussion on, and it’s not long before testicles are being (metaphorically) poked. I’ve asked him about Kim Jong Phil and whether these more humorous projects are a kind of corrective to the serious self-scrutiny of the others.

It’s true. I’m utterly fascinating.

Oil on canvas, 30 × 40 inches

From the series Kim Jong Phil

‘They’re lots of things. Kim Jong Phil‘s a joke, but also a very candid discussion of what tools and fuel I require to function as an artist.’ At this point his self-regard alarm seems to go off, and the impish side makes an appearance. ‘It’s also funny,’ he reflects with satisfaction. ‘The art world isn’t big on funny, so naturally, as a pathological contrarian, I feel the need to poke things in the balls.’

What ties all the work together, it seems to me, is a very complex and refracted interest in the self and what it’s made of — in memory and in how we look at ourselves. In interviews he’s joked about his narcissism, but if it’s narcissism it’s not of any straightforward kind.

‘Having been raised in England, talking about oneself is not done, so I joke about it because some part of me finds it slightly embarrassing. In fact, of course, it’s actually completely ok to speak about yourself in your work, as long as you’re unflinching and cruel about it. Beautifully cruel, maybe, but cruel certainly.’

From the series Maybe

Maybe, a prosthetics-heavy series depicting a range of possible old-ages for Toledano, chimes perfectly with that. Funny, uncompromising, haunting, elliptical, it’s all about the artist — yet in fact is about what the artist isn’t, what he might be, what he’s afraid of, what he finds ridiculous or pitiable or moving.

From the series Maybe

‘I suppose it’s about the dark unpredictability of life. I was focused on myself but also everybody — my fears, the shadows, the unseen turns that life has in store for most of us.’

Its heaviness does seem touched by levity, though, I suggest.

‘Well, I guess I used that work to heal myself of those fears. At the risk of sounding like Deepak Chopra, at the end of three years of working on it I felt lighter. So yes, not unmitigated gloom.’

Was the autobiographical, self- and family-documenting focus always the direction in which he saw his work moving?

‘Not at all. That all started with Days With My Father. Up to that point I’d certainly never thought for a minute that anyone would have any interest in my life, or in what I had to say about it or what it was teaching me — because why would they, really?’

From the series Phonesex

From the series A New Kind of Beauty

Graham Greene is supposed to have said that a writer or artist has a sliver of ice in their heart, suggesting that to turn life into art takes a kind of cold dispassion. Does Toledano ever feel during the autobiographical projects any sort of artist’s guilt over the use of the painful stuff of people’s lives — even of his own?

From the series Maybe

‘No,’ he says, ‘because I never consider the audience when I work. That doesn’t come into it, so the fact that it feeds into the project doesn’t change the experience itself. It’s not even that it doesn’t happen, but that it couldn’t — if I become self-conscious I become self-censoring and afraid, and if you’re going to do personal projects, you can’t be afraid.’

The interview over, I think more about this last response, which puts me in mind of an indelible image from Maybe. An ageing Phillip Toledano sits alone at a table; there’s a birthday-cake on it, and balloons on the floor. His smile is fixed and artificial (but aren’t all of ours in those moments?), and the first time I look at it it seems to me that there’s an edge of panic or of despair in his eyes — possibly both. But it’s such a haunting image precisely because of the way that the tacit fear and despair refuse to confirm themselves; I come back to the shot and find a kind of optimism in it instead. Oddly, it seems all the more fearless and confrontational for its humour and ambivalence. Phillip Toledano, narcissistic self-deprecator and wryly upbeat tragedian, strikes again.

From the series The Reluctant Father

From the series A New Kind of Beauty

Abu Ghraib coffee table, 2008

From the series AMERICA THE GIFT SHOP