It’s almost 20 years since I walked toward the huge glowing orb of Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project at the Tate Modern. That massive sun in a cavernous industrial setting was a remarkable sight for a young art fan, but more so a turning point for the art world, which now — with the rise of social media as a further catalyst — seeks ‘experience’ above all; exhibitions now ticketed events with stadium gig sensibilities. From restaurants to fashion stores, sport events to websites, Experience™ is inescapable. But hasn’t that always been the case?

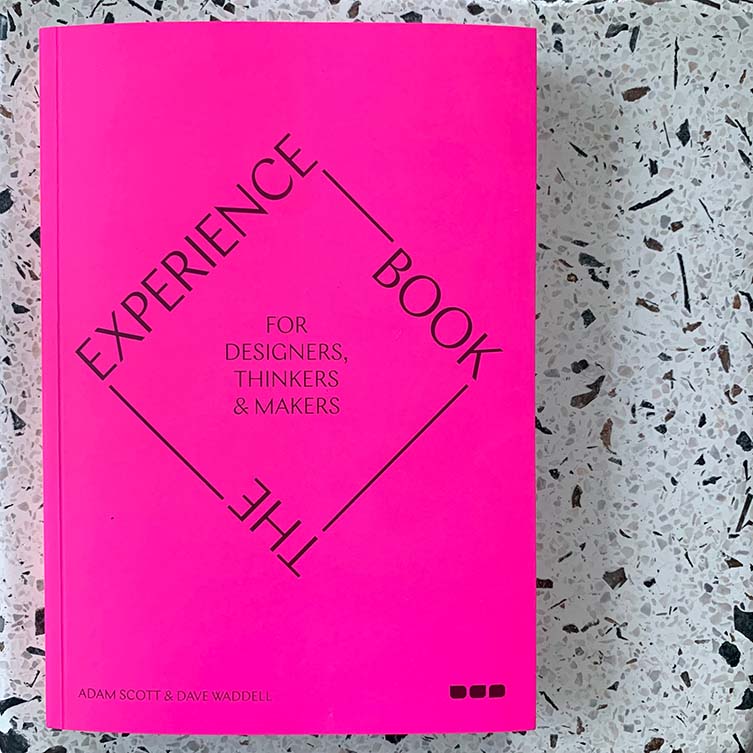

Because, you know, experience is just living. Being alive and doing things together. It’s innate to our selves that we make and enjoy and live through each and every experience we or someone else creates. A new book by a good friend of mine and a good friend of his attempts to dissect this in detail. It begins with a Keats quote that says what I just said but a little more eloquently: “Nothing ever becomes real till it is experienced — even a proverb is no proverb to you till your life has illustrated it.”

In The Experience Book, Adam Scott and Dave Waddell take us through the history and meaning of experiences and how one seeks to design them. They explain how humankind has been storyboarding for more than 35,000 years, and spin their readers through a dizzying array of examples that take in national parks, Olympic Games, the world’s best restaurant, queer subculture, Burning Man, Pokémon Go and so much more. It examines how and why we respond to experiences, the science and the emotion, how our minds process memories and how that can be manipulated by thinkers, designers and creatives. It’s fascinating stuff.

Waddell is a long time friend of We Heart, us having met many years ago drinking exceedingly expensive whisky in a hot tub in Iceland. He’s since wrote about one of disco’s most important producers, his dad’s natty safari suit and a Croatian festival among other things. He’s also a thoroughly lovely chap with a heart of gold, but my admiration for the best wordsmith to have graced these pages does not bias my opinion of what is truly compulsive reading for any fan of design, doing or thinking.

Having just produced one of the most exhaustive documents of experience design to date, I delve a little deeper into what it all means, questioning Dave and Adam about their understanding of design, experience and the human psyche.

We know quite a bit about the Waddell side of The Experience Book equation, but nearly nothing about the Scott side. Adam, tell us a little about yourself, your background, and how you came about to write a book about experience design. Dave, chip in as you see fit.

Adam: My part begins with a childhood playing in the ruins of the first English landscape garden, which then moves to my studying architecture, and which I quickly came to believe was too much about destinations and not nearly enough about journeys. From here, it was all about exploring what I believed a more generous idea of design, at first at the Royal College of Art, and then in eventually founding the experience masterplanning agency FreeState, which allowed me to bounce between brand-building and city-making. The Experience Book is a result of this backstory and the constant challenge of taking on the function-first – at least how it has been interpreted in the mainstream – approach to design.

Dave: My part in this story begins when FreeState began to work on these massive tradeshows they were involved in. I was still at the time a teacher, but was in the process of transitioning to become a writer. In my ignorance, I had always thought the only way to make it was either to write a bestselling novel or to become some sort of a Mad Men character, writing ad copy on the back of napkins and the like.

I had no idea that there existed an entire world out there happy to pay me to write stuff for its websites, products, pitches, and so on. FreeState asked me to write some product descriptions for their first show. I don’t think they ever made it past the Sony speak-like-Sony filter, but that was the start of what is now a 12-year working relationship. We’ve most of the time working together on scripts for live events, exhibitions, and brand experiences – and on all sorts of stuff in the built environment.

Let’s begin by asking why this book and why now?

Dave: In the early years, we wrote a blog called ThemePark – later Adam’s Apples. Super short blogs, it covered a whole bunch of stuff, historical and contemporary. It got a bit of traction. People seemed to enjoy the insights. Actually James, I remember that you featured the blog, and you even came along to one of our FreeDinners, which invited people from all kinds of backgrounds – academic and commercial – to share their work and thinking. Anyway, we always thought, if we had the time, we’d use the blog as a basis for writing a book. That was the genesis of The Experience Book, from my point of view. However, I know that Adam had always, as he says, wanted to develop a theory of experience design.

Adam: Walking through London today, I see adverts across tube stations and buses, billboards, and signs around the city – ‘The Peaky Blinders Experience’, ‘The Ultimate Co-working experience’, ‘Experience King’s College London’, ‘Experience More Morocco’, etc. Clearly, we seem to greatly value the designed experience in all walks of life. We wanted to write a book that somehow captured that, that seeks to get into that ‘Experience Era’ question with as much depth and breadth as possible. Which meant going deep into why and how the designed experience shapes the way we think, feel and act – what it is, in other words, to be an experiencing human.

It meant having a sense of how ancient and universal it is, from the shaman in the cave to contemporary theatre to a workplace or university and even to the city. We’ve been doing this for 35,000 years and the book tries to encompass the way we’ve filled time and space with our ideas, ideas that have made us what we are today.

So, before diving in, some key definitions: What for you is the meaning of ‘good design’? And what does ‘experience’ mean?

Adam: We love William Morris’s guidance on the useful and the beautiful. We are also big fans of Dieter Rams and his Ten Principles. Both approaches leave space for the personal interpretation and iteration of the user, as they also speak to the ambition for a whole ecosystem outlook, a universal design foundation if you like. This book super-charges that ambition: we go deep, we go broad, and we seek to connect with an aspiration as old as human consciousness – that need to put ideas in the world.

Dave: ‘Experience’ is a much bandied about word, and used to sell anything from phones to holidays to cities. We have the ‘experience economy’ and the ‘user experience’, and ‘experience’ is everywhere and anywhere. Thing is, ‘experience’ is fundamental to being conscious, and without consciousness, there is no concept of experience.

What does this mean? Having a sense of ourselves as experiencing subjects is also what makes us have a sense of others as similar experiencing subjects. We have a sense of ourselves and others, and having this sense – or meta-cognition, an awareness of being aware – is what allows us to know we exist. It is this knowing that we design for.

The book is broken up into The Guidebook and The Sourcebook. I know they appear to be what they say on the tin, but what does each section of the book do, and why have you chosen to structure it like this?

Adam: At least two years of this seven-year writing journey saw us trying to work out how best to organise the thing. If we were to successfully wrap our arms around this huge story, we needed a clear framework. The breakthrough was imagining we were standing shoulder-to-shoulder with our reader-makers: we would talk about the front-of-house nature of the experience, and we would go far and wide looking at fine examples, then we might pin them up on a wall and draw links between them so that we might better understand the connections and anomalies – this became the Sourcebook and is by nature very discursive.

In order to better understand why these designs were so effective, we realised we needed to go into each with great depth – into the back-of-house – and look at why and how they work. Like the Eames Powers of Ten, this meant exploring the workings of the mind, understanding the power of narrative, and tracing the development of the human as a cultural species. It also meant providing a kind of manual for making these designs, which is where the chapters on strategy, design, and action come from. This became the Guidebook and is by nature more didactic.

Dave: To add to Adam’s point about back-of-house / front-of-house. As we began to research the book, we realised that we really needed to dig into what makes humans so adept at putting ideas into the world, and what – which is the other side of the same coin – makes us so susceptible to those ideas.

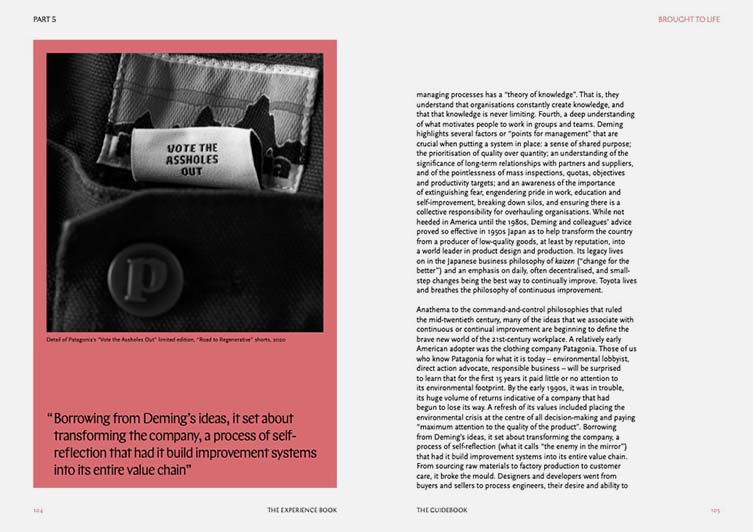

Knowing this (however lightly, however broadly) really helped when it came to explaining our intuitions about the examples in The Sourcebook. For example, the story – The Pursuit of Satisfaction – about how Lidl, after ten years of failure, managed to turn Sweden onto the supermarket, is on the surface of things a story about a brilliantly designed campaign.

James, you may remember it. I’ll be quick: Lidl opened a pop-up restaurant headed up by a Michelin starred chef and serving only food made from ingredients sold by the supermarket. Knowing that any reference to the supermarket would sink the campaign, it called the pop-up Dill, banned all mention of the name ‘Lidl’, and only revealed the truth at the end – once everyone was raving about it. It appears that the pop-up successfully persuaded the nation to change its mind about Lidl, and the supermarket made its first profit in Sweden in a decade.

Beneath the success of the design, however, lies the fact that it managed to subvert an unfounded bias – that the supermarket was ‘cheap’, sold inferior quality food, and was frequented by only people struggling economically – by exploiting that same capacity for bias, using our propensity for status-seeking as vehicle.

I should say that neither of us are philosophers, cognitive scientists, evolutionary biologists, or experimental psychologists. We’re acutely aware that there is a lot in the book that skirts over things that people have dedicated their entire lives to. We hold our hands up to being amateurs dabbling in worlds we barely comprehend. We just couldn’t help ourselves.

Crown Fountain, Chicago © Conchi Martínez.

Anyone involved in the business of putting their designs – or as you say ‘ideas’ – into the world knows how important it is that the vehicle for doing so is a good story. What it is about the narrative that we humans find so compelling.

Dave: The late American psychologist Jerome Brumer used to speak of two ways of knowing the world: through science and through storytelling. The first is descriptive and incomplete and necessarily truthful. The second is simply believable and whole and not necessarily truthful. You’ll note that information couched as a story is much more memorable and generally much more compelling. This is increasingly thought to be because we constantly model and remodel our sense of self, others, and the environment through narrative frameworks. It’s how we make sense of ourselves – as ‘stories in the making’, says the cognitive neuroscientist Steven Brown – and it’s how we make sense of the world.

Basically, we’re wired for story, which is why a well-told story generally beats a set of numbers or data points hands down when it comes to which one’s more believable. Its why science co-opts narrative to get its truth out into the world, and it’s also why we are susceptible believing things that are utterly untruthful. There’s a ton of other stuff we could go into, but I fear I may be becoming a bore.

Adam: From an experience design perspective, we’re interested in the kind of journey of involvement and belonging that gives shape to – and is given shape by – the self-as-protagonist that Dave’s alluding to. Great designed experiences are held together by narratives that get ever more active and participative with each step. We make these stories come into being as we engage in the experience. In the book, we try to show how this works via Chicago’s Crown Fountain: that is, how it attracts, involves, and gives a sense of belonging, the way it acts on the individual and the individual acts on it.

It enables very personal narrative-mediated experiences which, when we surface from them, we ‘re-present’ – to borrow a word from the psychiatrist and writer Iain McGilchrist – to ourselves as stories. You don’t have to have been to the Crown Fountain to have experienced this: we have all been a part of something similar – it might have been called a show or event or lesson or dinner or performance or trip or adventure or holiday or artwork. It’s the designed experience as action.

So, when it comes to designing experiences, you divide the process into ‘strategy’, ‘design’, and ‘action’. On the face of it, this would appear to be a reasonably uncontroversial approach. And yet, when the reader digs into the meat of the book, you make a number of counterintuitive points. For example, you remark at the beginning of the chapter on strategy, ‘that there is no such thing as strategy’. Throughout the book, you say that ‘everyone is an experience designer’. In the chapter on action, you appear to advocate that ‘strategy’ and ‘design’ are preceded by ‘action.’ What do you mean?

Dave: I’ll take the strategy bit. We’re being disingenuous when we say that there is no such thing as strategy. Of course, there is. However, we’re pushing back on two things. One, that strategy is always necessary. It’s not. It’s necessary when there’s a problem to solve. This may sound obvious, but there’s no need for strategy when there are no problems to solve, and life isn’t just one problem after the next – at least not in the sense we’re using it here.

Two, that strategy is a fixed plan. Any strategy worth its salt has the capacity to adapt to the real world of evolving events. It needs to be loose, super flexible. There is no plan, only planning. We’re not saying anything new: Lawrence Freedman’s wonderfully comprehensive work Strategy is the go-to text for anything on strategy. Otherwise, what we have to say about strategy is reasonably mainstream: it’s a constantly updated hypothesis based on evidence and given shape and direction by a vision.

Adam: I think we’ve begun to cover off the idea that everyone’s an experience designer. On one level, this is simply what is called human-led design, the idea being that design isn’t simply about function. If a design is to work, it needs to serve the communities it is for, and if it is to do this, then it needs to be born of and driven by the myths and rituals that underwrite and help form and reform the culture(s) that bind these communities. This is much more than simply consulting people’s needs and wants at the beginning of the project: it’s involving them throughout and beyond.

On another and connected level, it is understanding that a design is no design without people. Again, this sounds stupidly obvious, but if you think about those ‘landmark ‘buildings commissioned by cities which land in real-world communities as well-sculptured aliens and end up winning loads of design awards and yet remain empty of people, you get the idea. Any design, a building included, is brought to life by people, and people change, which is why the design needs to build in contingency for change. The Victorian warehouse, which is full of redundant space (and therefore wonderfully adaptable), is an example of such a design.

On action preceding strategy and design, this is simply the reality – rather than the reverse engineered story – of a given design. We may begin with strategy, but its frequently informed by just doing, in the form of prototype, pop-up, meanwhile state, all of which acts as exactly the kind of feedback loop that allows the design to develop. In this respect, no design is ever finished: the ‘designed experience’ is not a product, at least not in the finished sense. It is an ever-evolving platform for collective action(s).

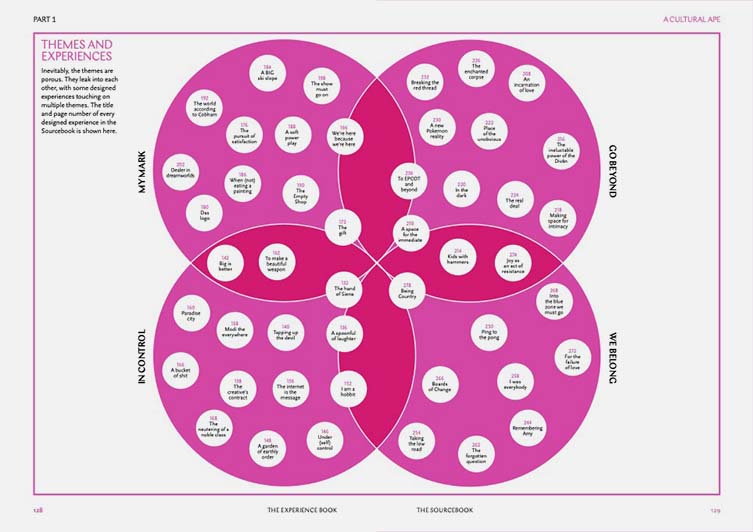

The Sourcebook is divided into four themes, each theme being a chapter of a dozen or so experiences. The four themes are: In Control, My Mark, Go Beyond, and We Belong. Can you say a little about the meaning of these distinct categories and why these and not any others?

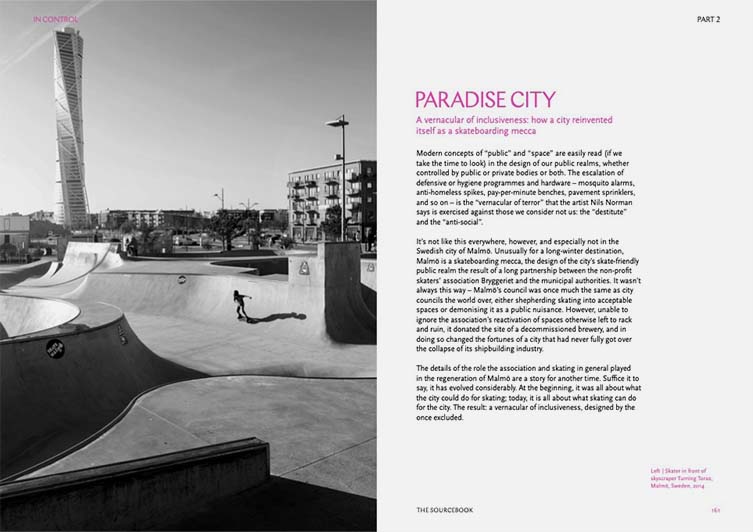

Adam: How best to order a Sourcebook that frames the last 35,000 years? So many ways to order, and we tried many: by scale, my date, by geography, by participant, by host. In the end, we decided to order by intent. At first, we thought we might try twelve archetypical categories. Eventually we settled on four: either experiences designed to exercise control, to stamp individual identity, to facilitate transgression, or to foster belonging.

Dave: We’re clear that while we think these our universally true categories or themes, they’re by no means the only ones, and may well not be the best ones. The other thing to note is that we’re also aware the choice of experiences is limited by the limits of our own experience and knowledge, which is why we see whatever we have here as the beginning of a long conversation, and invite anyone to bring their own ideas to the experience-design table. The more the better!

Museum of Old and New Art (Mona) © Jeff Owen.

The entire book is a super-rich collection of historical and contemporary designed experiences – some small, some large. Do you mind sharing a few of these – perhaps examples that go some way to proving the thesis of the book.

Adam: We include a story on Universal’s Harry Potter experience. We begin by quoting writer and film critic Neal Ganbler: ‘You look at the parks Disney created. The only two figures who could do that are God and Walt Disney.’ I’m not sure whether this is tongue in cheek or what, but it’s probably exactly this level of world-building confidence that had Disney executives turn down JK Rowling and her demand for total creative control of a ‘Wizarding World’.

Basically, Rowling didn’t want a world – with its fantastical histories, geographies, species, and technologies – that belonged to the imagination of the hundreds of millions of fans who had read her books and seen the films diluted or infected by the world of Coca Cola and like. Universal eventually capitulated to her demands in the most uncompromising of contracts, which included an injunction that Wizarding World ‘be a world class level themed area unsurpassed by any other themed area in any destination theme park in the world’. This was no empty pledge: any deviation noted by Rowling, and Universal had just ten days to set it right before she pulled the plug on the whole thing.

Any corporate lawyers out there will no doubt be madly scribbling notes – this was unheard of and, what’s more, Rowling was absolutely right: Wizarding World and its iterations around the world have been a cash cow.

Dave: James, I think you and your readers will enjoy the story of David Walsh and the Museum of Old and New Art (Mona), which is in Tasmania, and is described as the southern hemisphere’s answer to the Bilbao Guggenheim.

Walsh set up one of the world’s most successful gambling syndicates, but it seems that being unfeasibly rich didn’t do it for him, and he sunk all his wealth (and more) into a museum that has done wonders for the island’s economy. The museum’s schtick is sex and death and Walsh portrays himself as a hater of anything that smacks of art criticism and collector / gallery snobbery. He’s so outspoken about his own sexual ‘triumphs’, it’s difficult to know what and what not to take seriously.

He’ll say things like not giving a fuck about where he was born, not knowing whether any of the art at Mona’s any good, and that the museum’s just his ‘fitness marker’, which allows him to ‘bang above my weight’. We think the key to everything he does is to be found in the fact that he’s driven by a personal quest to find out ‘why I do what I do.’ The museum’s a machine for understanding the machine of life itself – and, as we say, everyone’s invited along for the ride.

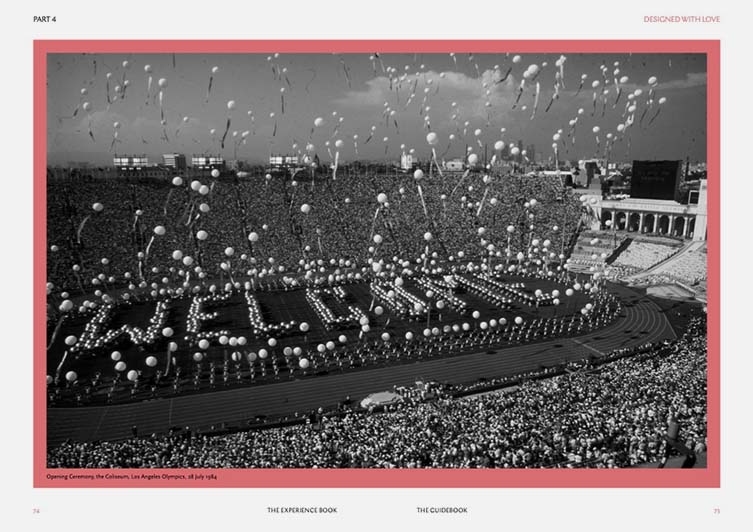

Adam: We run the whole chapter on design through the 1984 LA Olympics. The LA Olympics has described as being one of the most wondrous sporting spectacles in the modern era. It sold 5.7 million tickets sold, had two billion viewers, and included 221 events in 75 venues spread out over 3,500 square miles. It has been the experience-making benchmark for every Olympics since. But it could so easily have been the very last Olympics.

The previous two had nearly bankrupted their host cities, and LA won the right to host it in 1984 by dint of being the only city in the running. Nobody at the time wanted to touch the Olympics. It was a poison chalice. Yet it managed on a paltry budget and made a profit (which was ploughed into a sports foundation that has given the world the likes of the Williams sisters), and nothing – not a single cent – came from the public purse. How the organising committee managed this covers off most of what we mean by the business and meaning of experience design: people, programme, place – get these right and all else will follow. It was brilliantly done and brilliant for it.

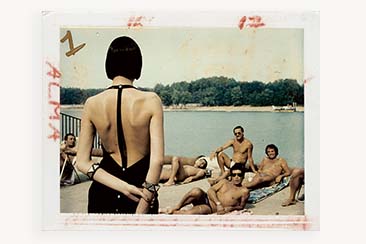

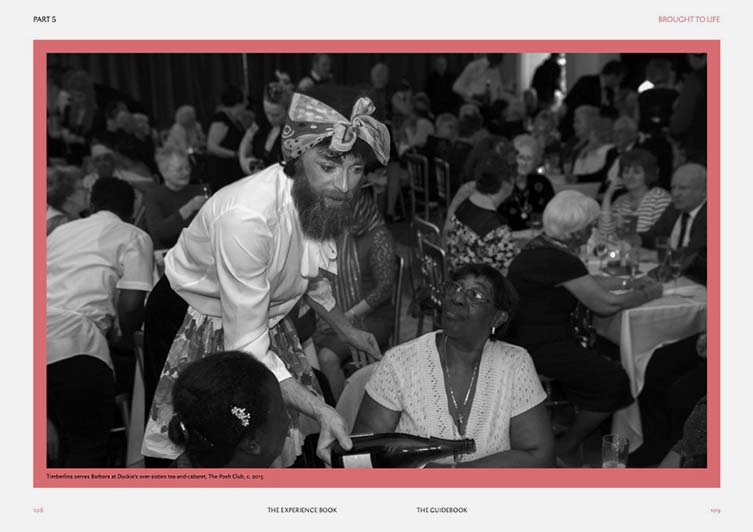

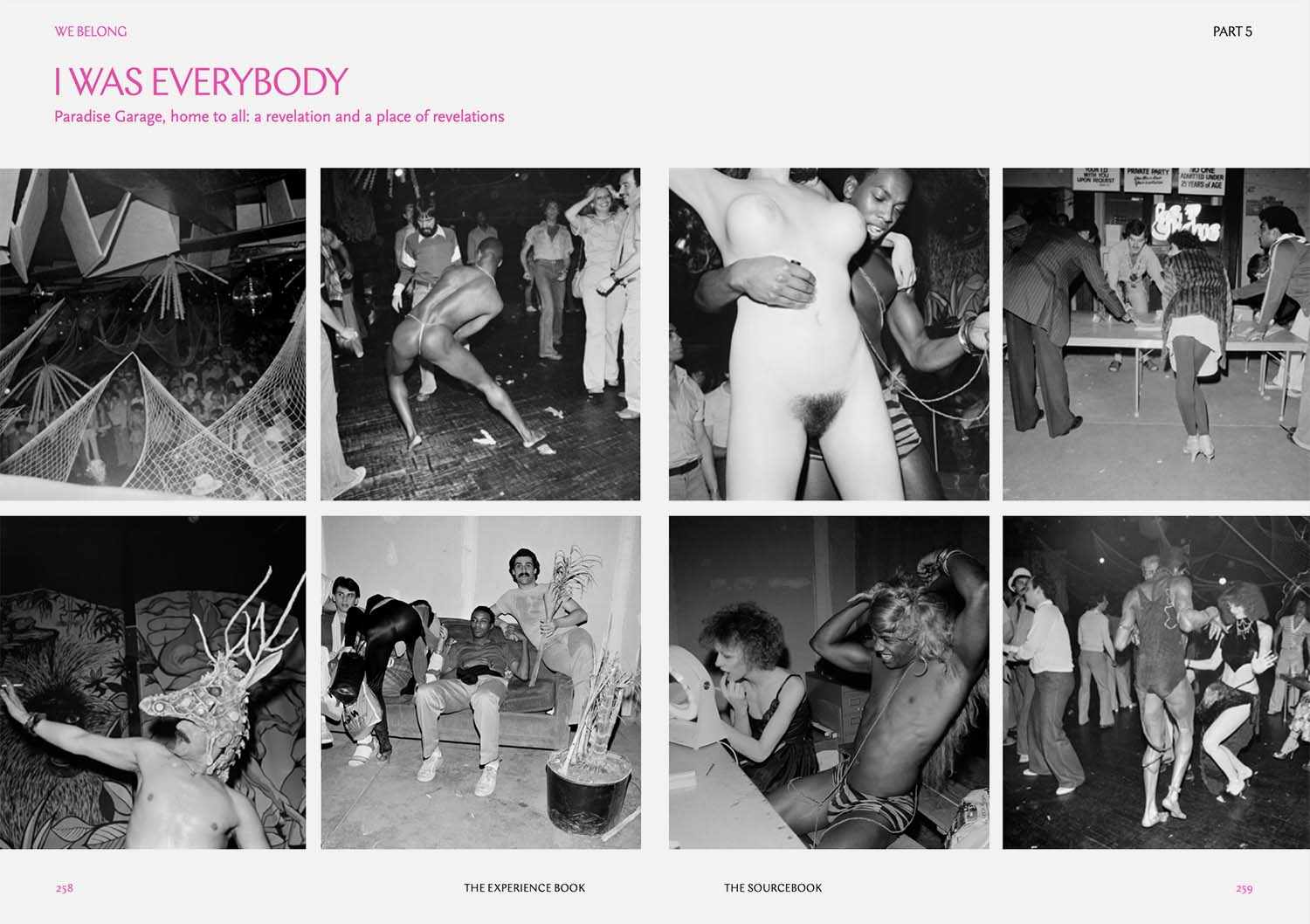

Dave: In the book, we argue that the very best of experience designs are ‘machines for belonging’. These are the designs capable of changing lives and one such design is the London-based queer performance-based Duckie, which was set up in 1995 as a Saturday club night at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern in London. A night dedicated to booze, dancing, and acts or turns, it deliberately turned its back on the mainstream gay scene, which its chronicler-in-chief Ben Walters describes as being dominated at the time by ‘single-sex environments, house music, male gym culture and cruising, ecstasy, and, when it came to performance, strippers, and traditional drag queens’.

The night’s still going today, and it has many offshoots, including the Duckie Homosexualist Summer School and The Posh Club, both of which are joyous outreach ventures or what Walters calls ‘homemade mutant hope machines,’ and which, he says, routinely create ‘queer futurities’ that have the capacity to change peoples’ lives. It’s just fucking amazing – there’s no other word for it.

Paradise Garage Photos © Meryl Meisler.

Finally, it’s clear throughout the book that ‘experience design’ for you is fundamentally important from a moral perspective. Can you say why this is the case?

Adam: We wrote this book during the pandemic. The lockdowns were the most expansive of social experiments we have ever witnessed, the most compelling of cautionary tales, as we saw what happens when the designed experience is not just turned off, but banned, outlawed even! And as we retreated from the public realm, and found ourselves stuck in an ever-repeating cycle of entertainment from box sets and hospitality from dark kitchens, we were denied a world we had taken for granted.

If you’d walked Old Compton Street – or any other historical part of any city – during full lockdown, you would have become incredibly aware that all these heritage buildings meant nothing without anyone to bring them to life. We are hungry for those experiences and more discerning than ever before. This book is the manual for diving into those experiences!

Dave: But not just any designed experience. What we have tried to be clear about is that the designed experience can be for the good and for the bad and for everything in between. What, therefore, it is that makes us so amenable to the designed experience and the tools used for creating that experience can also be used – harnessed, activated – to create and perpetuate the very worst of experiences.

While progress – moral and technological – may have given us the capacity to live relatively peacefully in groups of millions, it also has us sleepwalking into relative catastrophe, especially in terms of climate change and the collapse of the ecosystems on which all this progress relies. The pandemic, a relatively benign one, was a shot across the bows of humanity: we have the capacity to design our way out of what could be just round the corner, but it means getting our shit together.

Adam Scott and Dave Waddell’s The Experience Book will be released 27 September 2022 and is currently available for pre-order at www.blackdogonline.com. You can follow them @the_experience_book.