There’s always a sense of contingency to Arlene Gottfried’s photographs. Frequently joyful, they also carry poignant risk.

That is partly testament to the spontaneity the shots manage to transmit and evoke: the flipside of spontaneity, of course, is a sense that the world is full of such moments, most of them slipping off unrecorded — unnoted — into obscurity. By telling us how spontaneous and quicksilver the world is the photographs make us see how much of it is lost.

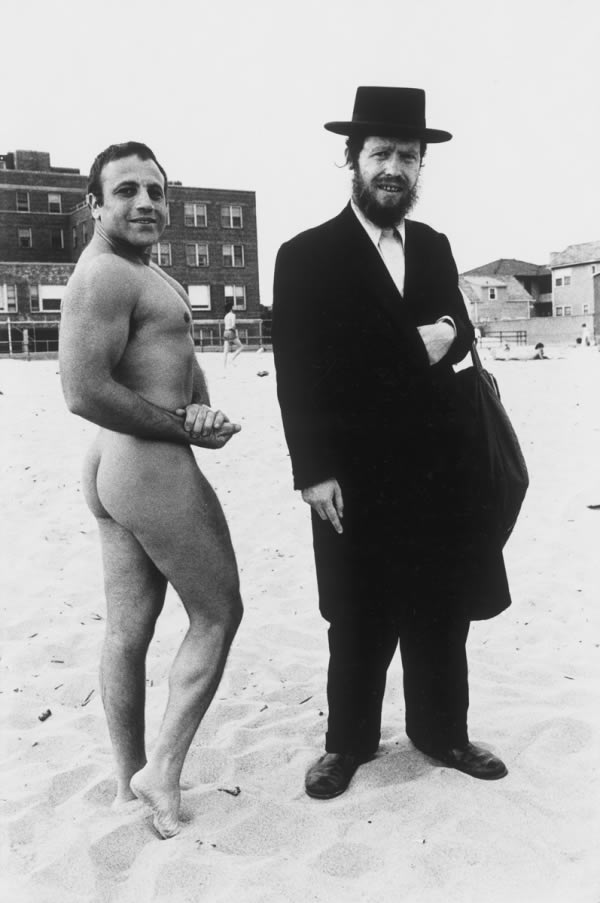

Hassid and Jewish Bodybuilder, 1980,

from the book Sometimes Overwhelming

Alternatively, sometimes the sense of risk in Gottfried’s work is to do with the admixture of humour and mournfulness, the refusal to draw any clean aesthetic or emotional lines. (See Hassid and Jewish Bodybuilder, for instance, with its humour and sense of camaraderie coexisting with such palpable potential for misunderstanding and alienation.)

If you know anything about Gottfried herself, though, the feeling of hazard also arises because the work hasn’t always found the audience it deserved; it has sometimes seemed on the verge of slipping off into obscurity, unrecorded like those moments we were talking about earlier.

Take her 2014 book Sometimes Overwhelming, for instance, which collects swathes of her black-and-white street photography from the 1970s and ‘80s. It represents an incredibly rich profusion of documents of the New York — in particular Coney Island — that has been Gottfried’s lifelong home, a place that it wouldn’t be going too far to say has now all but disappeared (and is not on the cusp of a resurgence if property developers have anything to do with it, which they emphatically do). It’s an important New York book, then — yet it could easily not exist.

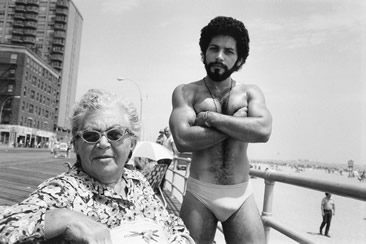

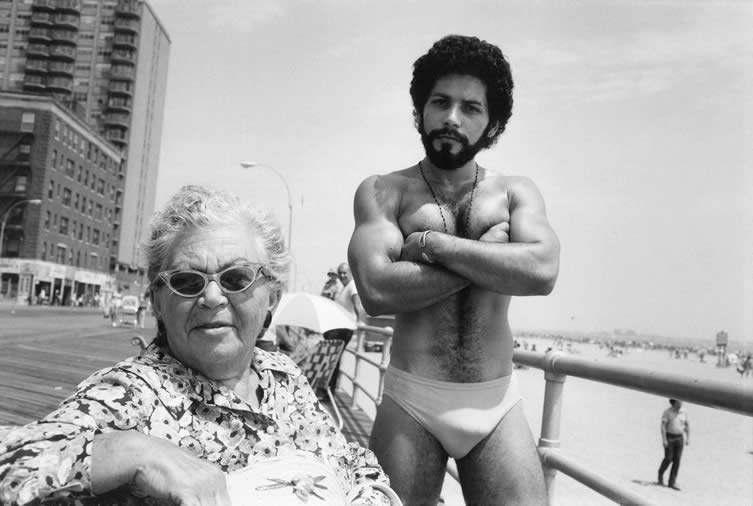

Angel and Woman on Boardwalk, Brighton Beach, from the book Sometimes Overwhelming

Isabel Croft jumping rope, Brooklyn, 1972

from the book Sometimes Overwhelming

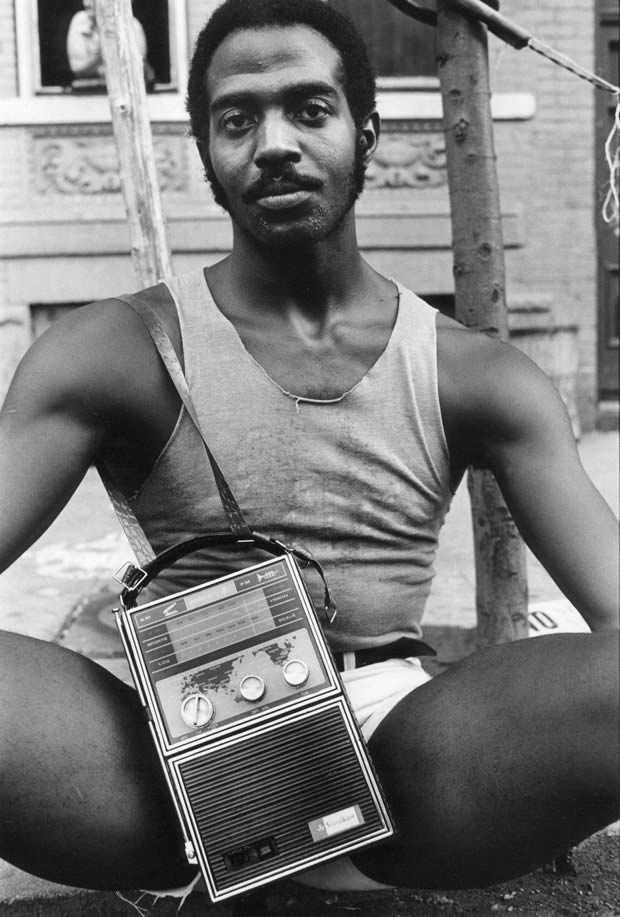

Guy with Radio, East 7th St, 1977

from the book Sometimes Overwhelming

‘There were just a lot of photographs taken over the course of the decades, while my commissioned photographic work was going on alongside. The book only happened because Maria Mayer Feng, who designed it, came over to my house to program my website.

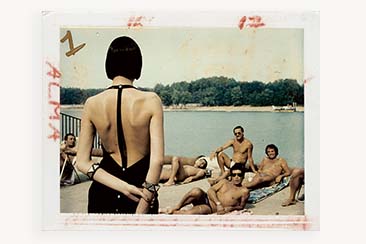

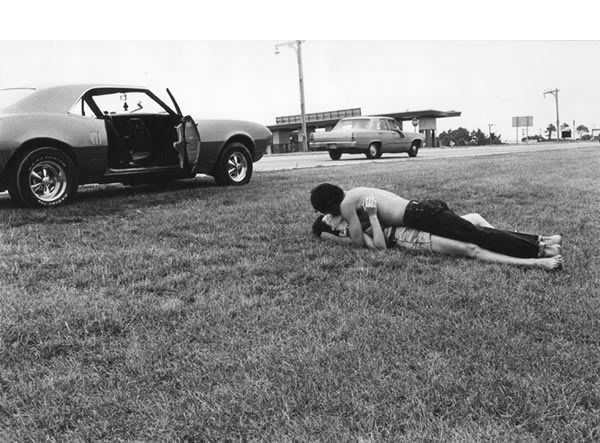

Kissing on the Highway, Queens, 1980

from the book Sometimes Overwhelming

When she saw the black-and-whites she told me she also designed books and asked if would I consider doing a book with her. Since most of these images had never been seen and I had no plans for them, it was a great offer, so we started making the selections.’

I’d prompted the story by asking whether or not she’d always planned on eventually making such a book. Just to be clear, she hadn’t?

‘No, I never planned for a book of Sometimes Overwhelming. It was chance.’

A not uncharacteristic near-miss, and presumably just the kind of thing that leads her to describe her career, half-jokingly, as ‘a pain in the neck.’ That’s of course not to say that the career hasn’t also been an impressive one: her work has appeared in and on the New York Times, the Village Voice and Life among many others. Nonetheless, it was only the publication — and accompanying gallery show — of Sometimes Overwhelming that brought the new and welcome level of attention she now enjoys.

Puerto Rican Day Parade, from the book Bacalaitos & Fireworks

Bubbie’s Living Room, from the book Mommie

Karen and Cherry Blossoms, from the book Mommie

That book was followed last year by the publication of Mommie, a collection of more recent work documenting three generations of Gottfried women, in particular Arlene’s mother as she declined in health. Very different indeed to the previous volume, Mommie shares its predecessor’s eye for detail, unflinching sense of truthfulness and ability to feel out unexpected joys.

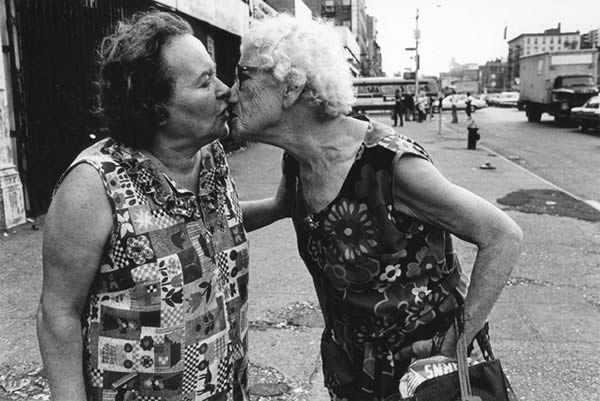

Mommie kissing Bubbie on Delancey Street, 1979

from the book Sometimes Overwhelming

In connection with this, I suggest to Gottfried that there’s a further way in which her work is risky, that part of the power of it comes from her willingness to find the beauty in things without prettifying them or denying their pain and ugliness. That’s a fine line.

‘I agree with your interpretation of the quality of looking hard at things that are not necessarily obvious or pretty. That’s usually the crux of my photography I would think — I don’t only photograph what’s beautiful, although I can appreciate it. The Mommie work was particularly difficult to do, but there was no escaping my mother’s illness and her decline, and so I chose to document it on film. The essay ends with the birth of my nephew, though, so it ends on uplifting note.’

The entire oeuvre is also characterised by a palpable sense of place. Much of it seems distinctively ‘New York’ — even Rodeo, a collection which looks as if it should have been shot in Montana or Texas, in fact was taken at a rodeo just over the river in New Jersey — and it’s true that Gottfried is a dyed-in-the-wool, old-style New Yorker. How big a part has the city itself played?

Push Ups El Barrio, from the book Bacalaitos & Fireworks

Buick on East 6th Street, 1985

Sunbathing, West Village, NY, 2006

‘I was born and raised here. It’s where I first started taking photographs, just of friends and family in the places that we were. New York is home: when we were young we hung out with our dog in my father’s hardware store, meeting all the customers, the community. Coney Island was a great place, close to the beach and the rides, where we went a lot.’

Zapps Burgers

She’s adamant, though, that it’s not a matter of an autobiographical sympathy or exclusive bond between artist and subject.

‘It’s what I’m accustomed to and what I photograph,’ she says, ‘but I can just as easily travel to somewhere completely different and photograph that, too.’

She’s a professional, in short, as her career in commissioned photography amply shows. After so many years in that industry, experiencing pretty well every aspect of it from being an assistant to shooting covers for the NYT magazine to publishing books of her own work, with much of that experience garnered in times before our relatively enlightened own, Gottfried gives an impression of supreme unflappability. She’s seen it all. As a final question, though, I ask her about her views on Instagram-culture and its effect on the professional photography market.

Cartwheels in Hydrant, from the book Bacalaitos & Fireworks

‘There is an excess of photography available electronically these days,’ she says, flatly.

Would she care to go further?

‘The digital world is here to stay. I have no views about it, really. I would say though that along with all those difficulties there is more equality of opportunity for women now than when I began, and that can only be a good thing.’

Unflappable, as I said, and that’s no doubt been one of the qualities, doubtless hard-won, that’s helped Gottfried achieve the career she’s had. Nonetheless, following the recent surge of interest it seems she might be able to do with a little less of it in future. Here’s hoping.

Snow White, from the book Bacalaitos & Fireworks

All photography © Arlene Gottfried

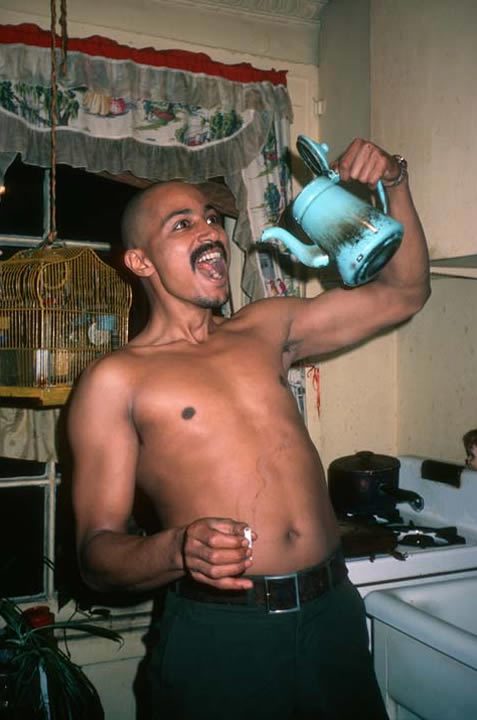

Coffee Pot, from the book Midnight