Stand at ground level at Park Hill and you can almost smell yesterday’s pub food drifting out from the cafés and hear the ghost-clank of milk floats the decks were once designed to carry.

The Grace Owen nursery sits on its small patch of tarmac, as it has since the early sixties, with plastic toys stacked behind the windows and parents tugging small children in through the door.

Behind it the estate climbs the hillside in long, stepped blocks. From certain angles it still looks like a single continuous wall, a kind of cliff made from brick and concrete, running along the ridge above Sheffield.

When the estate opened, that cliff was meant to be progress. The old back-to-backs and yard toilets were cleared away. In their place came nearly a thousand new flats, each with its own bathroom, central heating and a front door opening onto a broad deck in the sky.

Park Hill Estate, Sheffield, 1961 © Roger Mayne Archive / Mary Evans Picture Library.

The architects gave those decks the names of the streets they had erased, and even relaid old cobbles, so residents walked familiar words and stones at a new height. The decks were level enough for milk floats to run along them and wide enough for prams, gossip and the odd bike race. For a while, if you listen to the stories of original tenants, it worked.

Children played across the decks in all weather, neighbours knocked on each other’s doors, the pubs and shops on the ground level were busy.

Then the cracks appeared. Lifts broke and stayed broken too long. Rubbish piled up in corners everyone assumed were someone else’s responsibility. The long decks that had once felt like streets began, in certain stretches, to feel like corridors. Security budgets shrank.

By the eighties the wider city knew Park Hill less as a flagship of new housing and more as a byword for trouble. Reporters came for pictures of boarded windows and broken glass. The huge blocks felt heavy in a different way.

Even then, there was a kind of presence to the place. The line from The Smiths appeared on one wall, sprayed in white down a concrete panel: “All those people, all those lives… where are they now?” People photographed it against orange skies. It sat there, half lament, half statement of fact.

Park Hill then.

Park Hill now.

The next chapter is now well known. The estate was listed, saved from demolition and handed to developers. Grey balconies acquired coloured panels. New entrances opened with key fobs and intercoms, and brochures began to talk about “urban living” rather than postwar reconstruction.

Students and young professionals moved into refurbished sections. Rents and sale prices climbed well clear of what council tenants once paid. Other blocks remained untouched, still carrying the stains and scars of the leaner years.

Walk through it now and you move between versions of Britain. One corner yields a new café with bare brick walls, industrial lighting and laptops on every table. Two minutes away you can stand in a stairwell where the paint has not been refreshed for decades and the handrail still curls with the original finish.

A balcony might have newly installed timber, planters and folding chairs; two floors down another balcony shows nothing but a line of washing and a plastic crate. The tension between those worlds gives Park Hill its current charge.

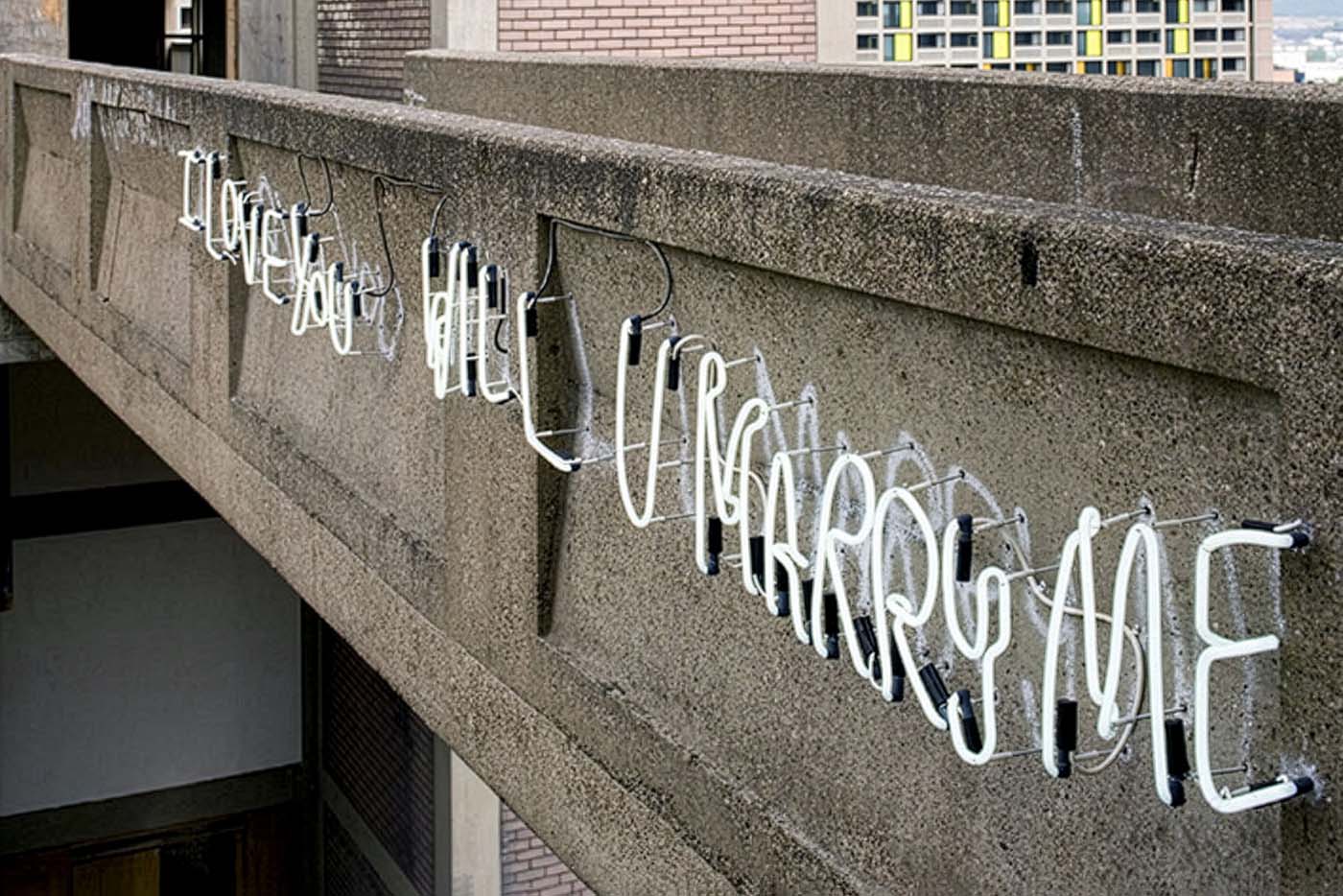

A new neon version of the iconic graffiti marriage proposal “I love you will u marry me?” pays homage to the estate’s past.

What keeps the estate from becoming a museum piece is the fact that large numbers of people still treat it as home rather than case study. Long-term residents talk about the new arrivals with mixed feelings.

Some are glad the place is no longer written off as a failure, others point out the shrinking number of social rented flats and the way certain stairwells now feel off-limits if you do not have the right key fob. There is truth in both positions. The estate has become more mixed and more expensive at the same time.

On an ordinary weekday afternoon you might see a delivery driver pushing a trolley across a deck, a teenager practising tricks on a scooter, an elderly woman pausing on a landing to catch her breath and look out over the city.

The new neon version of “I love you will u marry me?” glows on its bridge, a sentimental fragment from the estate’s own history, suspended above car parks and scrub.

Park Hill no longer embodies a single vision of the future; it shows what becomes of those visions once they have had to live with cuts, fashions, campaigns and compromise.

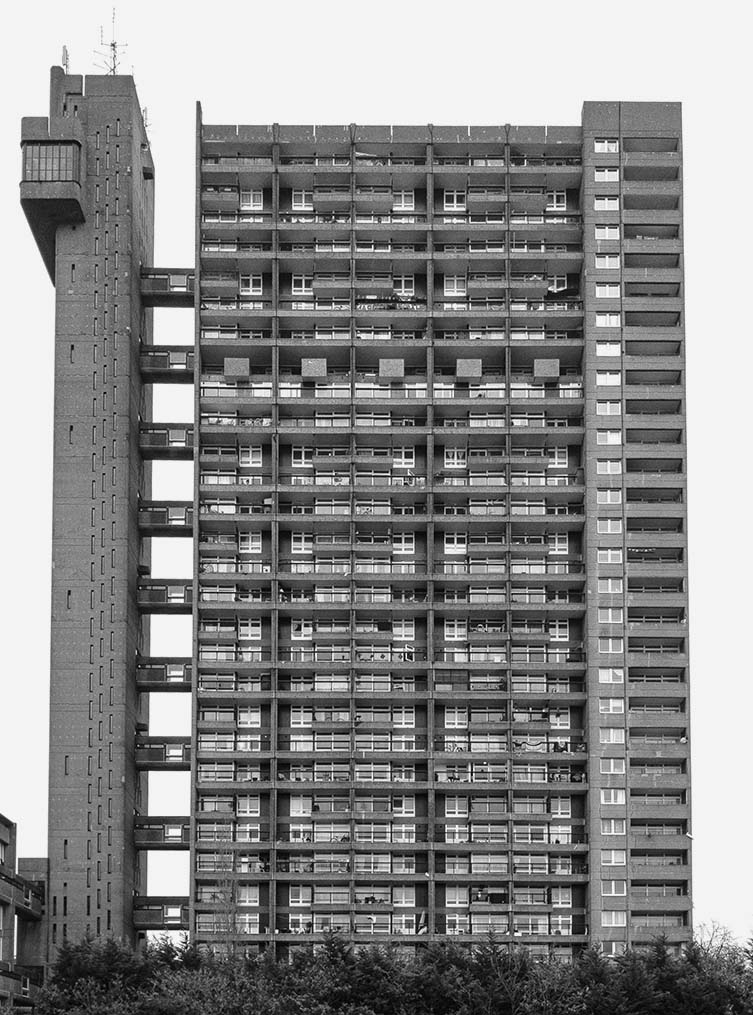

Trellick Tower © Richard Haas.

Trellick Tower stands almost alone beside the canal near Ladbroke Grove, a different proposition entirely. The main block is a tall, lean slab with rows of balconies; beside it, slightly separated, the concrete service tower holds lifts and plant rooms linked back by high-level bridges. The silhouette is severe and instantly recognisable.

Ernő Goldfinger imagined Trellick as humane high-density living. The flats are generous by contemporary standards. Each has a balcony, many are arranged as maisonettes with internal stairs, and the views across west London are broad.

The separation of service tower and main block was supposed to keep noise and machinery away from living spaces and leave space on the ground for gardens and play. As with Park Hill, the early publicity emphasised light, air and modern convenience for former slum dwellers.

The story turned quickly. By the late seventies Trellick had acquired a reputation for vandalism and worse. The access galleries that gave every front door a view also gave every passer-by a view of those doors. Strangers could move through the building unnoticed.

Break-ins, fires in bins, smashed lifts settled into the building’s public image. For many Londoners the tower stood for the whole perceived failure of postwar housing in one piece of concrete.

Trellick Tower © Ethan Nunn.

Trellick Tower © Steve Cadman.

The residents eventually forced changes, forming a tenants’ association that pushed for secure entry, for a staffed lobby around the clock, for repairs that lasted longer than a few months. Those efforts paid off. Crime fell. The tower stabilised.

Views from the balconies did not get any worse, and in a city where space tightened and house prices spiralled, some buyers began to look again. By the end of the twentieth century estate agents were talking about Trellick with the same language they used for converted warehouses.

Today, if you circle the base on a weekday evening, you see pairs of friends smoking near the entrance, a man taking a spaniel out around the block, a group of teenagers sitting on the low wall that separates the forecourt from the street and sharing headphones.

There are still stairwells that smell of damp and old cooking, but there are also tidy front doors with pot plants and smart bikes locked to railings. The transformation from notorious block to sought-after address is there in the small things: the type of pushchair in the lobby, the parcels stacked for collection, the queue for the lift.

Trellick’s concrete has aged in place. It carries stories of failure and stories of survival without much effort to tidy them. A tower built to house people who had few choices now appears on property wish lists. The building has not softened, but the way it is read has.

The Barbican Estate.

The Barbican Estate tells a more straightforward tale of privilege. From the start it was intended for middle-income and professional tenants in the Square Mile rather than for displaced workers. Its podium lifts residents above the street into a network of gardens, walkways and raised courts.

Three residential towers rise from this base, flanked by long terrace blocks wrapped around lakes and planted beds. Cars and buses pass somewhere below, out of sight and almost out of earshot. The flats are spacious, the finishes more refined, and the cultural centre that anchors the estate gives it an unusual status. Residents step out to concert halls and galleries as easily as others might step out to a corner shop.

Over time, Right to Buy and private sales have concentrated ownership. Prices have climbed into seven figures. The estate functions as a kind of fortified village with its own social code.

Inside a Barbican apartment © Anton Rodriguez via Barbican Residents.

If you sit near the lakeside on a Saturday morning you see how this plays out. A woman in running gear and wireless headphones appears from a glass door, carrying a yoga mat and a branded coffee cup. A small child pedals a balance bike in tight loops while a parent keeps half an eye on them and half an eye on a laptop screen.

A security guard stands near a discreet gate, talking quietly into a radio and watching delivery drivers come and go. The water ripples around stepping stones where someone has paused to take a photograph of the towers reflected in the surface. It looks peaceful, orderly, expensive.

Yet the Barbican is still Brutalist in bones and surfaces. The walls are rough-textured concrete; the bridges and staircases have the same frank structural language as estates that never received this level of care.

What sets it apart is less the architecture than its context and its long-term treatment. Where Park Hill and Trellick had to struggle for refurbishment and basic maintenance, the Barbican’s environment has been carefully guarded. It shows what Brutalist housing looks like when money and institutional attention remain in place.

Late afternoon at Park Hill. Light fades over the city centre below; the ring road hums in the distance. On one of the upper decks a child’s scooter has been left on its side outside a front door, its back wheel still gently turning from the last kick.

Two balconies along, a row of shirts hangs from a washing line, moving slightly in the breeze. Down by the nursery, a staff member locks the gate for the night and walks towards the tram stop.

The concrete frames all of it without saying anything about what should have happened here or what might happen next.

David Stewart has been a corporate content writer for nearly 20 years. Occasionally he writes journalistic and creative pieces. He lives in Glasgow. David is working on his first book of poetry.