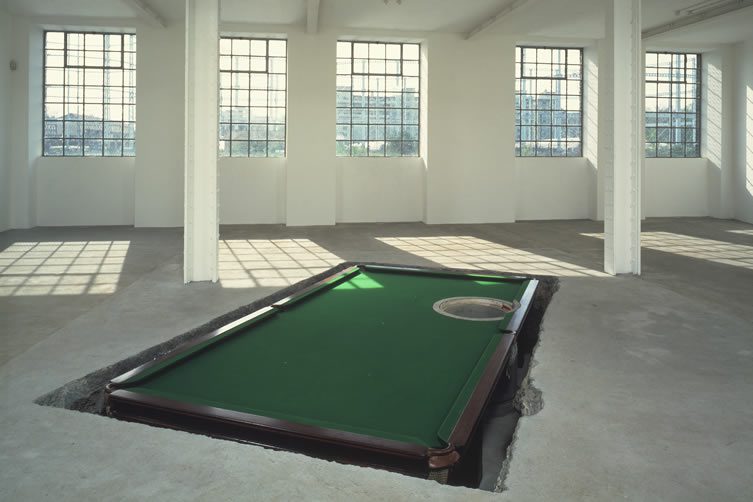

You know Richard Wilson’s work — even if you don’t think you do, you do. He’s perhaps best known for 20:50, his piece from the late 1980s that filled a gallery space with sump oil and invited viewers (via a partly submerged walkway) into the multi-planed, mathematically precise yet hallucinatory space thus created. (It’s been for years the only permanent installation in the Saatchi gallery, housed in a custom-built room.)

20:50

Saatchi Gallery, Boundary Rd, London, 1991

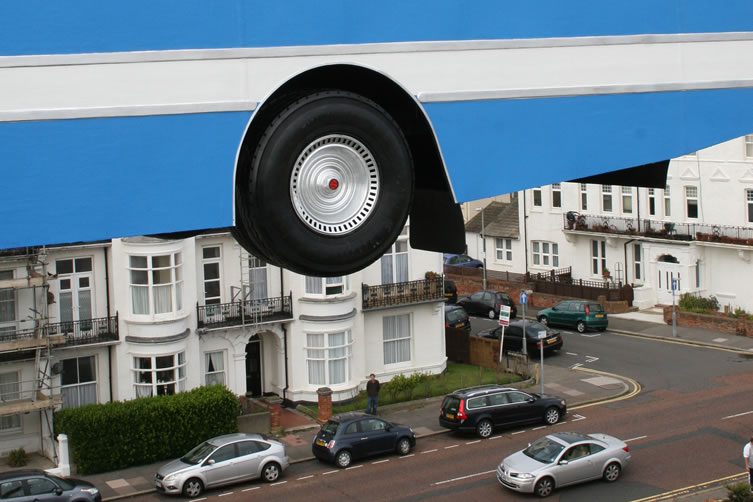

For Turning The Place Over, Wilson cut a huge section out of a concrete building-front in Liverpool and rotated it, miraculously conjuring a science fiction dimensional portal out of the lumpen reality of brutalist architecture. For Hang On A Minute Lads…I’ve Got a Great Idea, he balanced a full-size coach on top of a building in the unlikely surrealist surrounds of Bexhill.

They’re memorable, to say the least, but for me the most striking aspects of his work is that it makes me look differently at everything, as if the world is rigged with unassuming objects that might at any moment start to act oddly. When I ask him whether this is deliberate, though, he says not, or at least not exactly.

‘I believe the secret of your experience is that, though I look as if I construct, in fact I undo or de-construct. And by the deconstructive act of revealing you break the skin of an object and show that there’s much more than what you would assume going on under the surface.’

20:50

The pieces seem to engage the world as a place imbued with the fluidity of geometry and mathematics; somewhat incongruously, I was put in mind of them by the surreal CGI spectacles in Christopher Nolan’s film Inception, but of course Wilson’s work doesn’t rely on computer trickery (‘I find it impossible when its all in the computer. You don’t get that real response to problem solving’) and instead invades the material world. That said, what a Wilson piece does have in common with Hollywood productions is that it’s not cheap — not at all. His recent piece Slipstream, in Heathrow’s Terminal 2, is the longest and most expensive privately-funded sculptural work in Europe, and in terms of conception and execution can only be described as staggering. How on earth did it come about?

‘What I used to explain Slipstream to others was simply a verbal fictitious scenario: imagine filling the void of the Central Court of Terminal 2 with clay. Now imagine a small stunt plane moving through that mass of clay, somersaulting, spiralling, twisting and climbing. Once out the other side, imagine the vast void left by the plane’s path in the clay and fill it with fast setting plaster. Afterwards, excavate the hall of all clay to leave a suspended plaster form. Imagine what this solid but fluid shape of the movement of the plane through space could look like.’

Slipstream

Terminal 2 Heathrow Airport, 2014

Simple, right? The explanation does help to emphasis, though, that whereas it can seem as if his works are the embodiments of quite abstract notions brought to material life, in fact for him it’s never abstract. It’s more about understanding the material reality of things in profound and unexpected ways.

Slipstream

Terminal 2 Heathrow Airport, 2014

‘Understand what I was up to,’ he urges. ‘I never saw Slipstream as an abstract concept. I think it’s partly to do with understanding structures and how your world stands up. I liked the statement Fitzcarraldo gave in the film when asked how he intended to transport a steamship over a steep hill: “Like the cow jumped over the moon”. That’s how I try to think.’

And how does it work practically? What’s the process by which the reality-tweaks he sees in his head come to be made to the utilitarian spaces of our city-centres and airports?

‘It’s to do with not being afraid of grand schemes — and, of course, of having the right team around you to get you out of the fixes scale and size can place you in. I always develop an idea to the best of my ability, and then if the project requires engineering expertise then I approach one of several good engineering practices who’ve been sympathetic to my previous schemes. I would take to them all my drawings and models and we would spend time developing the necessary engineering. I enjoy the meetings with engineers especially when I bring in all my wood/card models — they’re incredibly democratic things.’

Hang On A Minute Lads…I’ve Got A Great Idea

De La Warr Pavillion, 2012

Works on this scale, in these everyday contexts, have as part of their appeal a sense of danger, I think. Can that sense of danger be a problem? That coach does look pretty precarious …

‘Well,’ he admits with a hint of humour, ‘Sometimes there is an element of reassuring a client that it won’t collapse … On the other hand, it can be a blessing, too. Once I’d proved that I could deliver work at this kind of scale the phone started to ring.’

Hot Dog Roll

Barbican Art Centre, London, 2006

Another notable feature of Wilson’s work is how irreverent it is, how unprecious: for all its surreality and insistent oddness, it seems profoundly democratic. He’s also a cultural magpie, on more than one occasion naming a piece after a popular song. It’s playful rather than ironic: One Piece At A Time is a good example, an installation named for the comedy Johnny Cash song of that name.

‘Well,’ he says, ‘for me its important to open parameters up rather than corral or close things down — it’s an inclusive approach on lots of different levels. And humour can be a very useful way into the sculptures for the viewer, as well. You need these as hooks for your audience. Alongside the scale and the spectacle, it’s all part of what I like to call the ‘wow’ factor.’

The ‘wow’ factor is very relevant. I’m interested in how he thinks about scale, since he’s brought it up a couple of times now.

Road Movie

Galleria Fumagalli, Italy, 2007

Water Table

Matt’s Gallery, London, 1994

Face Lift

Saatchi Gallery, London, 1991

‘The word scale is interesting with reference to my work. One has to ask “how big is large”, really: it’s all relative to what you’re trying to say and where you’re saying it. Slipstream at Heathrow is 78m long but is only supported on 4 of 11 columns that were offered to me as the site, so in fact it’s not that big for the space offered. One has to be sensitive to each site’s potential — sometimes the whisper is greater than the shout.’

And what draws him to these spaces and types of works?

‘I’ve spent the best part of 35 years tampering with architecture as my sculptural material, in order to disrupt our normal relationship with things in the hope of finding a new aesthetic potential. If that means being given a large architectural space or open area you find a scale or size that is appropriate for such a space. Basically’ — he says this nonchalantly, while singularly failing to convince me that I could ever consider doing anything like what he does — ‘space should not be intimidating. When I visit cities and see what man is capable of assembling as structures I know that my possibilities are opened up.’

A Slice Of Reality

Greenwich Peninsula, London, 2000

Turning The Place Over

Liverpool, 2008

As we near the end of the interview, I want to ask him whether he’s ever considered, or would ever consider, moving in a different — perhaps smaller? — direction with his work. It seems to me inconceivable that someone would consider at the beginning of a career that they might work at the kind of scale that Wilson regularly has, so it must have occurred to him.

‘Well, even now I work on a variety of different scales, and with sound as well as large objects and so on. But I’ve always seen myself as a formalist, working with known objects like architecture, ships, planes etc., and sometimes inevitably that can only be done at considerable scale. And as I said, once you’ve demonstrated that you can work on this kind of project you’re afforded opportunities that otherwise wouldn’t ever come your way. ‘Look,’ he finishes, ‘it’s that ‘wow’ factor I was talking about. If you can somehow challenge and tweak the viewer’s preconceptions of the world around them, then job done.’

Job, I think we can safely say on behalf of Richard Wilson, done.