Music is one of the integral parts of the Brazilian identity, to such an extent that any thoughts of the country, its culture, people and places comes with a mental samba soundtrack. From the overtly musical Carnival, to the dancing feet of its footballers, sometimes nicknamed the Samba Stars, everything seems to happen with a rhythm that is uniquely Brazilian.

But just as Brazilian music is one of the country’s main cultural exports, its roots come from cultural imports – immigrants from Africa, Caribbean influences, folk from the north country, and elements of American music both black and pop make up what Brazilian music is today. Now embraced around the world as a celebratory, feel-good artform, Brazilian music hasn’t always enjoyed such a cheerful time. In fact in the 1960s, a musical movement emerged that was the source of civil unrest and political persecution, as well as great artistic expression. Its name was Tropicália.

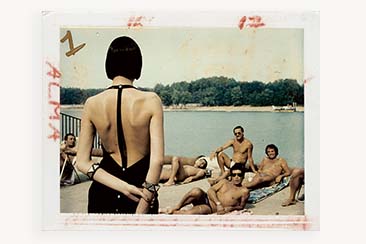

Back in the 1930s, samba music emerged as the national style, but later, in the 1950s, a new sound called bossa nova took up the baton and broke out of the country to become a global musical sensation. Air travel was taking off in a big way in the early 1960s, and when Joao Gilberto sang of the Girl from Ipanema in 1964, worldwide audiences lapped up the thought of idyllic Brazilian beaches and bronzed beauties. Meanwhile, in the real world, the country was in the grip of a military coup, with a dictatorship seizing power amid fears that the incumbent government was about to follow Cuba down the road to left-wing isolationism.

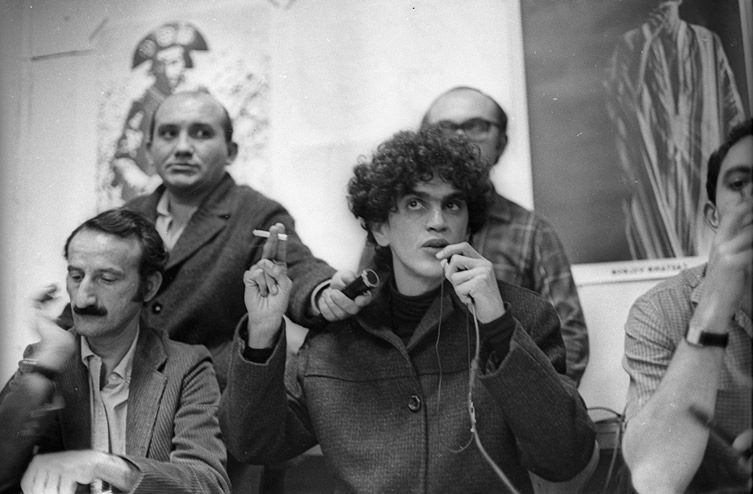

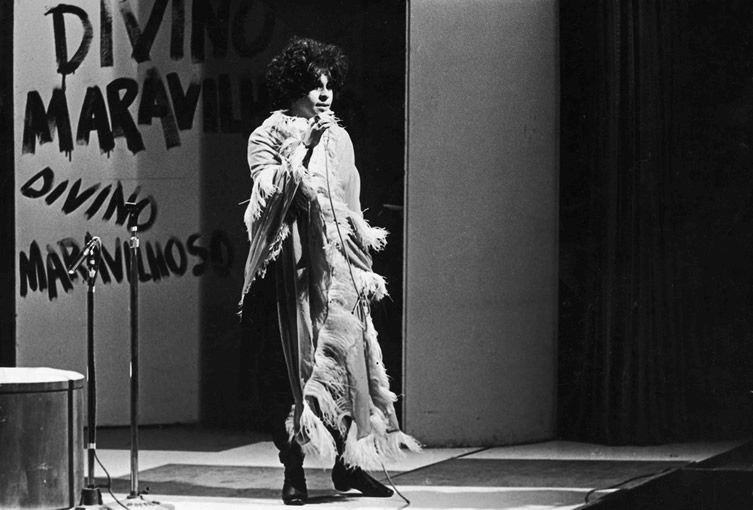

Caetano Veloso

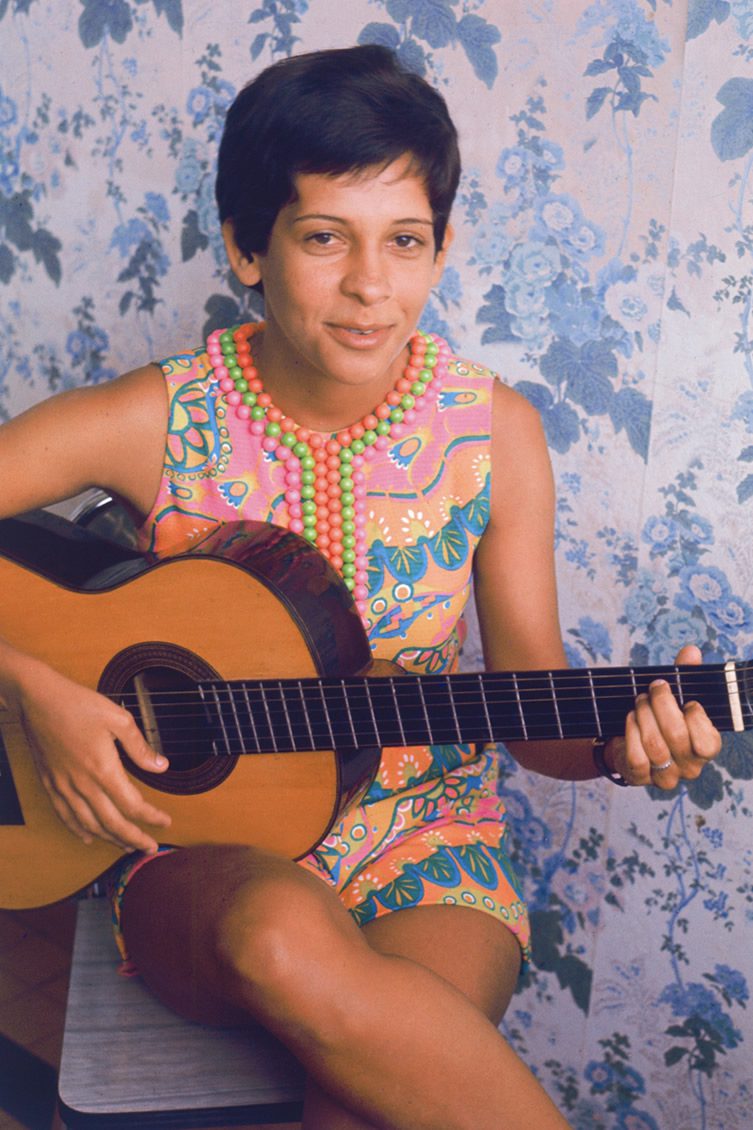

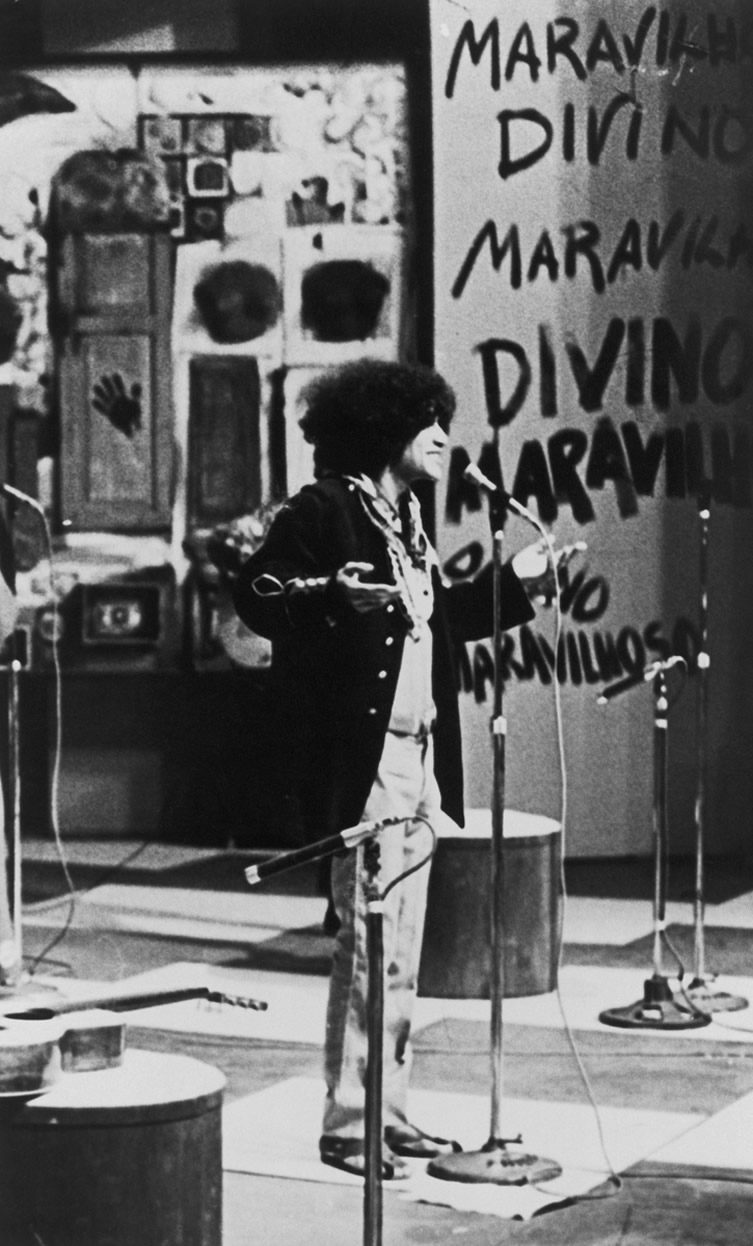

Gal Costa by J.Ferreira da Silva

Increasing industrialisation in the developing country drew tens of thousands of migrant workers to the major cities from the countryside, leading to the rapid growth of the shanty towns known as favelas. They brought with them the traditional sounds of their indigenous “indian” forefathers, such as maracatú from the north country, which blended with samba to produce a new sound in the hands of musicians such as Jorge Ben. His smash Mas Que Nada really kickstarted the international interest in Brazilian music, while at home, traditional Brazilian music festivals shown on the emerging medium of TV proved a huge hit with the locals. Pop imports by the likes of The Beatles were absorbed, and from this melting pot emerged distinct styles that supported differing political viewpoints.

Political protest was not, in 1967, repressed to a large extent. From the region of Bahia, a group of musicians emerged who blended bossa nova with pop, rock’n’roll and psychedelia into a style that became known as Tropicalia. Opposed to the military dictatorship, they were also against the left-wing ideologies too, and the music’s use of electric guitars – a direct influence of American music – infuriated the left as much as the anti-repression lyrics agitated the ruling military. Spearheading the Tropicalia movement were Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso from Salvador. Joining forces with more rock bands such as Os Mutantes and performance artists and poets including Tom Zé, the Tropicalistas, as they were called, began an exchange of artistic and political ideas. The results quickly incurred the displeasure of the authorities.

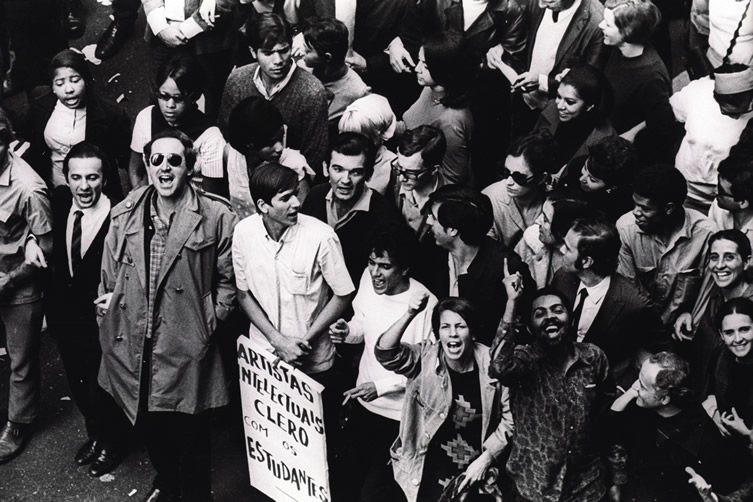

March of One Hundred Thousand, 1968

Photo, Campanela Neto

Gal Costa

Following the death of a university student at the hands of the military, the March of One Hundred Thousand was held on the streets of Rio de Janeiro in 1968. Gil and Veloso were front row figures, along with a host of other musicians from the left-wing, but it was only the two prominent Tropicalistas who were arrested by the government. A law had just been passed allowing arrest and detention without reason, and hundreds of suspected dissidents “disappeared during this time”. The pair, frightened but defiant, were held in prison for weeks before being transported back to their hometown and forbidden to leave. After four months’ detention the musicians were encouraged to get out of the country. They moved to London in 1969.

Although depressed at their exile, London wasn’t a bad place to find oneself at the end of the sixties. Musically, the big influences The Beatles and the Rolling Stones were at their peak, and other bands including Pink Floyd and Traffic were also providing interesting ideas for Gil and Veloso to absorb. Taking Tropicalia overseas, the two recorded in England—and in English—spreading the word about events back home and developing musically through collaborations at several key festivals and concerts, including Glastonbury in 1970.

It was 1973 before Gil and Veloso were allowed back to Brazil with the promise of freedom to make music without hindrance. The promises proved empty, however, as all live music still had to be approved in advance by the state censors and the Tropicália movement wasn’t ready to bow down by any means. Although they still regularly fell foul of the authorities, they didn’t suffer to the same extent as they had in the previous decade. The Tropicalistas were also back on home soil and perfectly placed to inspire the next generation of Brazilian musicians in the 1970s like Milton Nascimento, who would go on to be one of the country’s most successful musical exports, credited with popularising Brazilian music on the world stage to an extent that only the likes of Carmen Miranda had done before, back in the days of 1930s samba.

• Marcelo Machado’s documentary Tropicália, released by Mr Bongo, provides a fascinating insight into the people behind a very Brazilian revolution.

***

Caetano Veloso